A "Humanitarian Emergency" Among the Beja

In October 2004, three researchers from the School's Center for Refugee and Disaster Response set out for a month-long investigation into the lives of some of the world's most isolated herdsmen.

What the trio found among the Beja, living in northeastern Sudan, was grimmer than they had anticipated.

"It was like stepping back in time 1,000 years," says Shannon Doocy, a research associate in International Health, who made the trip with Alexander Vu, of the School of Medicine, and Pamela Marks, a former student.

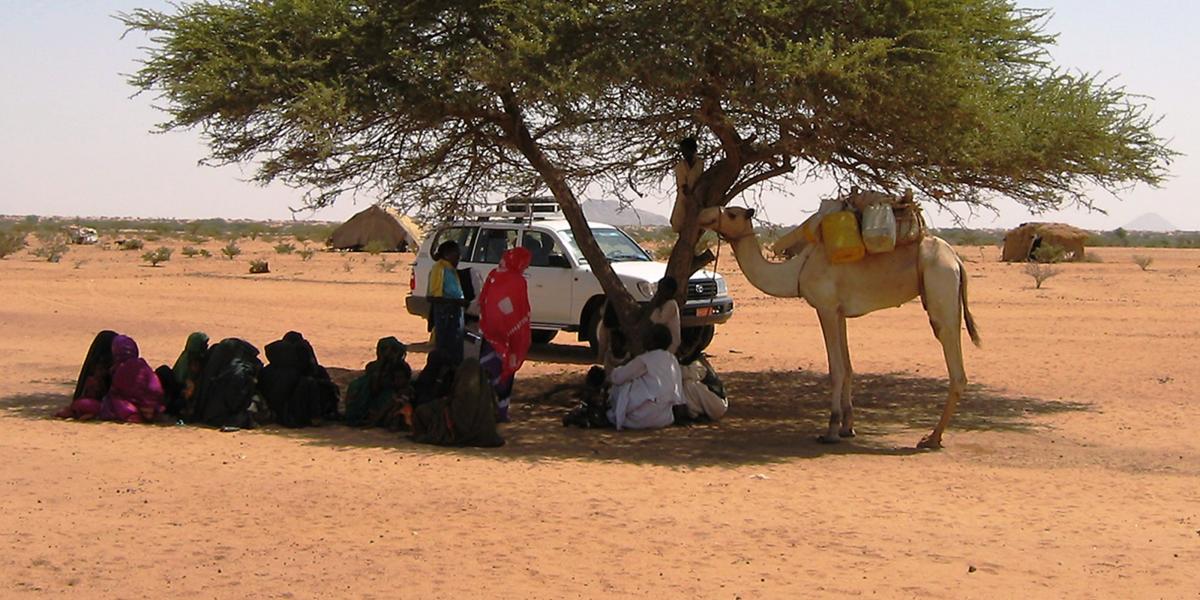

After a 10-hour trek into the desert, following dirt roads through an area pitted with land mines, the researchers came upon the first Beja settlement—a small community of tented huts and people with little food or water. Medical assistance was not available. Precious water came from a few wells in riverbeds that filled once or twice a year.

The Islamic herdsmen, caught behind rebel lines in the eastern Sudanese desert, had been cut off from food and traditional trading routes. "They had not received health or education services for years from the Sudanese government," says Doocy, PhD '04.

The team's experience underscores the challenges of delivering healthcare to some of the world's most vulnerable people. Africa is home to one-fourth of the world's refugees, people driven from their countries by war or natural disaster. And roughly 40 percent of the world's internally displaced people (IDPs) live in Africa, individuals made homeless within their own borders (see sidebar).

While refugees receive international aid, IDPs often are caught in war-torn countries with little outside help. Experts say 6 million displaced people live in Sudan, the largest single group in the world.

For Doocy, Vu and Marks—who had joined with members of the non-profit Samaritan's Purse International Relief to reach the Beja—the work was difficult. They quickly sent a few translators home because they couldn't support everyone in the desert with water carted in by donkey. A detailed questionnaire about food consumption was scrapped because a triple translation made it impossible to complete. (Only Beja men speak Arabic. Women had to communicate through men.) The age of the children was estimated through medical exam and anecdotal story, such as whether a child was born before a nearby hospital was bombed.

In two papers, under review for publication, the team reported that the Beja are in grave danger. Some 27 percent of the children suffered from acute malnutrition and 52 percent suffered from long-term deprivation. Mortality was more dismal: roughly 1.4 per 10,000 per day, for adults, five times greater than in the U.S., and 2.7 per 10,000 a day for children under 5, 12 times higher than in the U.S. These mortality rates surpass the international community's crisis threshold, classifying the Beja's situation as "a humanitarian emergency."

The international response to the plight of the Beja has been slow, compared to the outpouring of support shown to Asia's tsunami victims and the victims of Hurricane Katrina, Doocy says, adding, "The level of response in Africa is just not there."