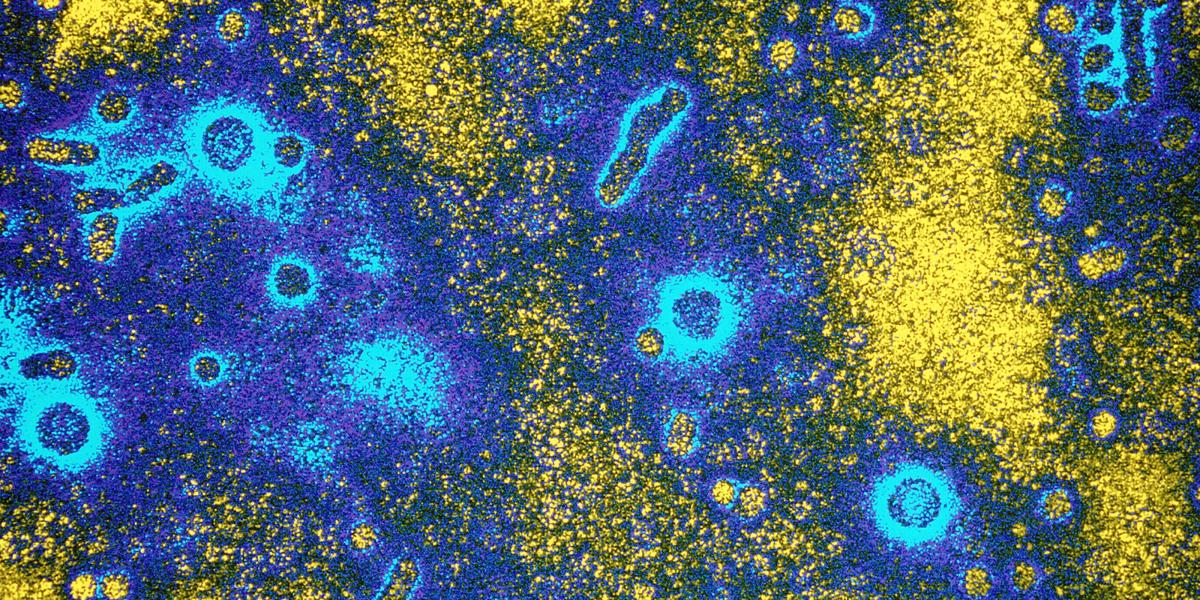

A New Way to Prevent Hepatitis B Transmission

Screening blood donors with a new assay may help to curb the spread of chronic hepatitis B.

Asian populations experience exceedingly high rates of hepatitis B infection of the liver, which can lead to cancer, cirrhosis and liver failure for some patients. In fact, chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection ranks as the number one cause of liver cancer in males in Thailand, a country with an inordinately high population of HBV-infected people.

Thailand, then, provided the ideal testing ground for Bloomberg School researchers to evaluate the effectiveness of a multiplex nucleic acid testing (NAT) assay to screen blood donors. While transmission of the virus is commonly linked to injection drug use, male-to-male sex and heterosexual sex, hepatitis B can also be passed on through blood transfusions.

The study results, published recently in Transfusion, showed the NAT assay to be reliable and cost-effective—and a more sensitive marker than current HBV screening methods. "We were a little surprised it picked up as many as it did," says lead author Kenrad Nelson, MD, a professor of Epidemiology at the Bloomberg School.

The study involved 5,083 blood donors from northern Thailand. Researchers used the NAT assay—which also screened for HIV and hepatitis C—on individual plasma samples. Specimens found to be reactive to the nucleic acid were then run with HIV-, hepatitis B-, and hepatitis C-specific assays to determine which virus was causing the reaction.

Six of the 5,083 donors who came up HBV negative using the current screening method (a surface antigen test) were correctly flagged as positive with the NAT assay.

Nelson recommends using the NAT assay in regions hard hit by HBV, assuming blood bank personnel can perform the test reliably, with few false positives and a rapid turnaround time. "You can take the infected blood out of circulation and limit the spread of the virus through transfusions," he says. "People should not be exposed to possibly fatal infections by being infused with blood."

There are also benefits for infected donors. Once identified, Nelson says, they can begin drug treatment, get tested for liver cancer (identifying it at an earlier stage), and practice safer sex measures to reduce the risk of transmission. Since the virus can be passed from mother to infant, any reduction in the number of cases is beneficial, he says.

Whether or not the NAT assay should be widely used in the United States is a matter of debate, Nelson notes. Given the country's relatively low incidence of hepatitis B—and that donors are already screened by other tests that could mark the disease—the costs of routine screening could be prohibitive, Nelson says.