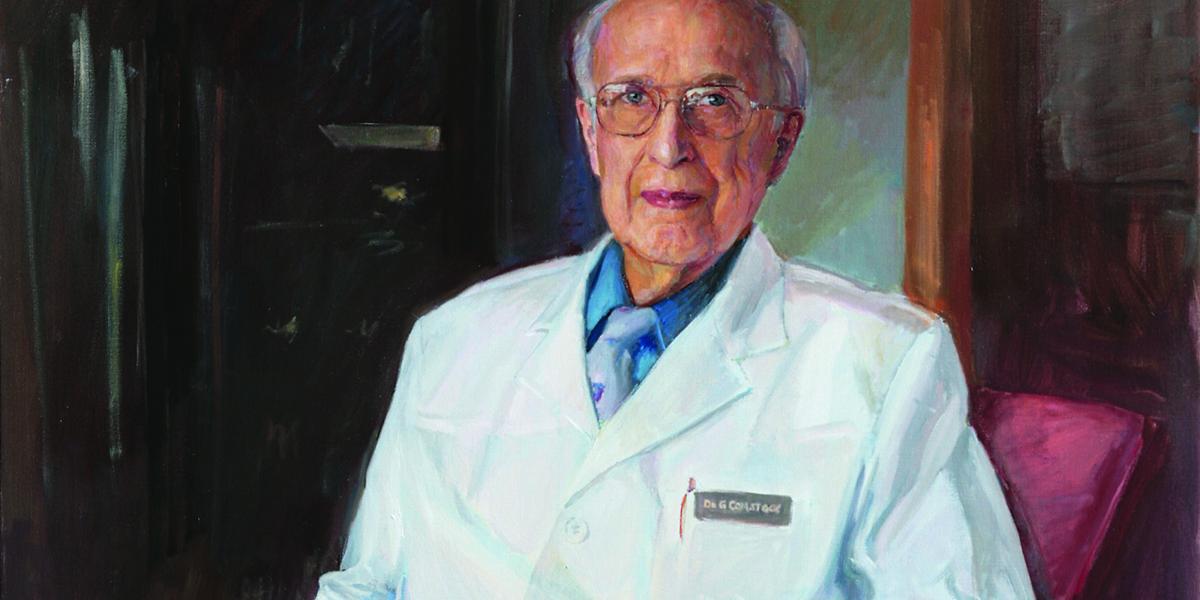

Always a Teacher: George W. Comstock, 1915-2007

In 1995, I sat down in a classroom (at Columbia University's School of Public Health) feeling a bit intimidated to be in the presence of Dr. Tom Frieden, who at that time was the Director of Tuberculosis Control in New York City. Each student was provided a foot-high pile of papers to read and discuss over the next several weeks. I started leafing through the papers and noticed that one name in particular appeared repeatedly: Comstock, Comstock, Comstock.

At that time, I knew nothing about tuberculosis and just a little more about epidemiology, but I quickly surmised that George W. Comstock, MD, DrPH, might be someone important. As one can imagine, by semester's end I had become quite familiar with Dr. Comstock's work, and it inspired me to volunteer in a tuberculosis laboratory in New York City. Soon thereafter, I pursued my interests in epidemiology and tuberculosis at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, where Dr. Comstock was a professor of epidemiology.

My wife had begun her doctoral work at Johns Hopkins a year earlier and had vividly described the many innovative and entertaining methods Dr. Comstock would use to randomly choose which student groups would present that week's laboratory assignments in the epidemiology courses. There were the toy soldiers with red paint on the bottom that the unlucky students would choose, and of course, Dr. Comstock would always take the time to relate the etymology of the word "cohort." The fortune cookie with the unlucky fortune hidden inside was always a favorite (I was only recently told by Dr. Comstock's son that Dr. Comstock would look through bushels of cookies until he found just the right one whose fortune could be plucked out with a pair of tweezers and replaced with one of his own). One of the more intriguing methods used by Dr. Comstock to choose the unlucky group was the walnut, the opening of which would reveal a metal ball. Finally, his use of the rock candy that revealed its true identity upon being bitten—the "sham rock" randomization method—always coincided with St. Patrick's Day.

While Dr. Comstock's senses of humor and irony were equally appreciated, it was his reputation for teaching that was legendary among students. When I arrived at Hopkins, I enrolled in his "Epidemiologic Basis for Tuberculosis Control" course, which he had been teaching since 1963. The course was different than any I had ever taken. Students would be assigned papers to read, then were randomly chosen to present these papers to the class. Most fascinating to me were the stories that Dr. Comstock used to highlight the historical significance of these papers. There always seemed to be more than just the tables and figures and results presented in the paper. We would learn why these studies had been conducted; what early or accidental discoveries had led to these studies; or the politics behind them. Of course, there were those papers for which additional graphs or figures had been generated, by hand, by Dr. Comstock. Poor, confused students would present a table or graph that had been attached to the paper only to discover after their presentation that Dr. Comstock had reanalyzed the author's data in a way that he thought more "appropriate."

When Dr. Comstock discussed the many papers he had authored, he would often mention the "survival bias" associated with the study. Of course, what he meant by survival bias was that he had outlived most of his coauthors, so he was left to write the paper. We all knew that he had led most of the studies, but his modesty rarely allowed him to acknowledge that—another of his endearing qualities.

The summer after I took Dr. Comstock's course, I became his teaching assistant. To this day, the most important learning moments that I have had occurred during the 10-minute walks I took with him from the classroom back to his office. In that brief time, he would comment on a topic we had discussed in class that day, always revealing an alternative point of view, often just for friendly debate. During one of those walks, he casually mentioned an idea that he thought someone "should look into," and that idea soon became my dissertation topic.

I began meeting with him routinely, and these meetings were always educational. Occasionally, we would disagree about how I should proceed, either with data collection or with analysis; and I will always remember approaching my advisor, Dr. Richard Chaisson, about such disagreements. Before I could finish relating my version of the debate, Dr. Chaisson would interrupt me and say, "Whatever way George said to do it is the right way." Not surprisingly, they both were correct.

Of course, when I would return to Dr. Comstock's office after having redone the analysis his way, he would always make me feel as if I were the one who had figured out the right way. This is also how he treated students in his class. Nervous students would stand in front of perhaps the most renowned epidemiologist in the world to present a paper, often a paper written by him. When a student would misinterpret some aspect of the paper, Dr. Comstock would ask the student simple questions in his relaxed manner, making the student feel as if he or she knew exactly what he/she was talking about and had gotten it right all along. His respect for students, and the learning process, was unparalleled.

I was recently asked, since I had become so close with Dr. Comstock and his family over the last several years, if I had any stories or insights that revealed a different side of him than that which his Hopkins students and colleagues had known. The truth is, I do not. To me, he was almost always the same. Whether in the classroom, in his office, at a barbeque in my backyard, or at his home in Hagerstown, Maryland, he was always teaching and telling stories. Yes, the stories changed and were sometimes more colorful when outside of the classroom, but they almost always had a teaching moment in them. What I will remember most about him is that in almost every conversation I ever had with him, I learned something new. That is what he wanted. He always wanted to teach.

My proudest achievement in my academic career, thus far, has been the development of an online version of Dr. Comstock's tuberculosis course. As Dr. Comstock's co-instructor over the last several years, I slowly introduced modernizations, always receiving his approval after initial hesitation. I then invited him into a recording studio to record his comments about his work and the many papers he often discussed in the course. He embraced this challenge, despite his failing health. During each session, sometimes scheduled between doctor's visits, he would sit behind the microphone and ask, "What do you want me to talk about today?" I would have pages of notes, and he had nothing in front of him but the microphone. I would introduce a paper or a topic, and he would start talking. We have incorporated these recordings into the online course. Now his voice and teachings will continue to be heard by future students, not just read in the literature.

I recently learned that Dr. Comstock's tombstone reads "Phthisiologist, Epidemiologist." Most people who see this will not know the meaning of phthisiologist. He wanted this written on his tombstone because people would read it, not know what it meant, and then have to look it up. A final teaching moment.

Dr. Comstock has inspired many people to learn, to ask, to achieve, to think, to be creative, and to teach. I will forever be indebted to him for his generosity and kindness towards me; I will always remember his intelligence and wit; and I will always strive to continue, in my small way, to bring his teachings to the students he held so dear to his heart.