Preparing for the Possible

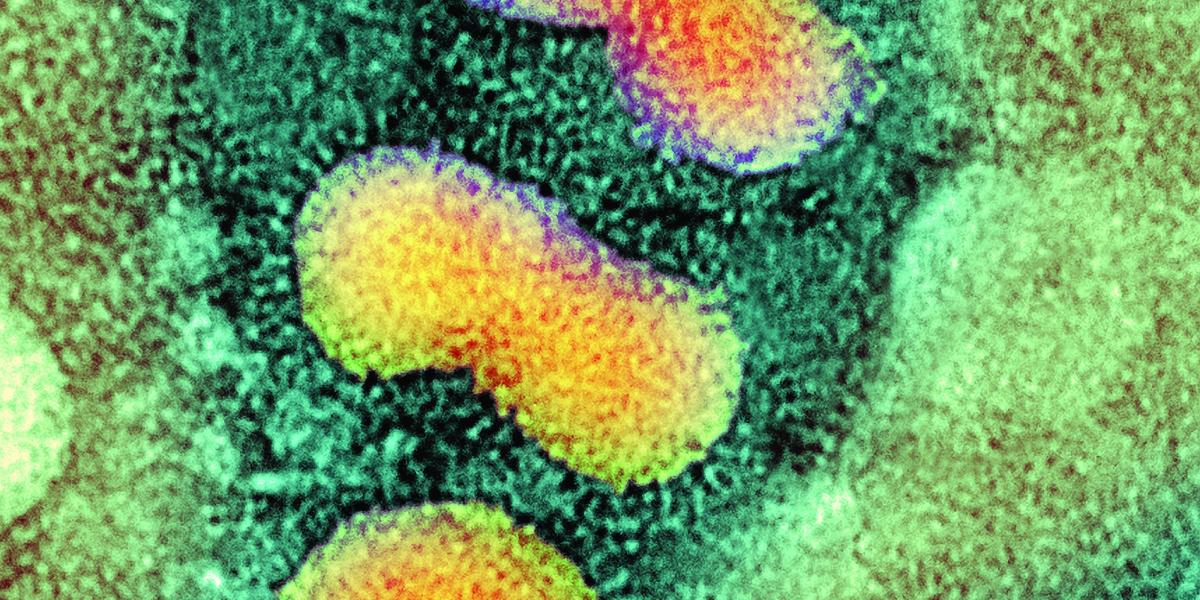

"A mutant influenza of nightmarish virulence."

"The most ferocious of man-eaters."

"A doomsday bug" that could kill 100 million people or more worldwide.

Bleak forecasts followed the outbreak of H5N1 influenza—the bird flu—in Asia in 2003 and 2004. Many public health authorities concluded it was only a matter of time before the virus or another like it would jump from birds to people, then from person to person, triggering a global pandemic. Governments, organizations and universities such as Johns Hopkins began planning for such an event.

Five years later, that nightmare has not come true.

While more than 300 people have contracted avian influenza since 2003, the virus does not appear to have acquired the ability to spread from person to person—a requirement for a pandemic. Some influenza experts now question whether it will.

In the face of such uncertainty, how do large organizations like universities or corporations prepare for the possibility of pandemic flu? Should they even devote resources to the effort?

Jonathan Links is convinced that they should. Despite the unpredictability of a future pandemic, he says, the consequences if one should occur would be so severe that organizations like Johns Hopkins must be ready.

Links, PhD '83, directs pandemic flu planning for the School and co-directs pan flu planning efforts for Johns Hopkins University and its health system. He is currently completing a pandemic influenza preparedness and response plan for the School, a 21-page document that has been three years in the making and gone through at least 30 iterations.

Planning for pandemic flu is incredibly complicated and more challenging, in many ways, than planning for other hazardous events, such as a toxic chemical spill or severe flooding. Unlike such acute events, pandemic flu could continue for months.

The plan relies on a global influenza-monitoring network involving the WHO, the CDC and other institutions. Health officials around the world regularly collect influenza specimens from patients and send them to labs for the high-level genetic and antigen analyses that will confirm a strain's identity.

The School's pan flu plan (and those for the University and health system) calls for three stages of response to the results of global influenza monitoring. The first stage corresponds to normal operations, when no cases of pandemic flu have been detected.

The second, or transitional, stage of the plan would go into effect if small clusters of pandemic flu (involving fewer than 25 people) appeared in different parts of the country. Hopkins officials would then halt classes and require students to leave campus.

A third, "critical" stage would take effect if one or more large clusters of pan flu (involving more than 25 people) appeared in the mid-Atlantic region. In that case, officials would close buildings to faculty and staff. Only essential personnel—such as workers who care for research animals, maintain freezers or service computers—would be allowed into Hopkins facilities. Those entering Hopkins buildings would be required to wear surgical masks.

More of a framework than a prescription, the plan outlines numerous tasks and responsibilities that must be covered in the event of a pandemic. Department heads and deans are then expected to decide how they will fulfill each one. Overall, explains Links, it emphasizes the need for continuing research and academic programs as best as possible, while assuring the safety of students, faculty and staff.

Researchers, for example, might have to put aside their laboratory studies, says Links, director of the Center for Public Health Preparedness and a professor of Environmental Health Sciences. But they could use the time to analyze data already collected. In terms of courses, the plan emphasizes the use of the Web and other technology used in distance education. Faculty should plan now for how they will deliver lectures, exchange course assignments and perform other academic tasks, using such technology, says Links.

"The planning process is very much ongoing," he notes. Each week, he learns of a new question or problem the plan must address. Just two of the most recent he's had to consider: If a critical stage of the plan went into effect, how would employees who do not have direct deposit receive their paychecks? They could not get their checks at work, since they would not be allowed in Hopkins buildings. Someone might mail them their checks. But who would that someone be?

Figuring out the answers to an endless list of such questions can be overwhelming, as well as distressing, to a scientist who admits to have a strong streak of perfectionism. In planning for pandemic flu, says Links, perfectionism may be an inappropriate standard. Stuff happens. Unanticipated events and problems arise. So he's taken to heart a colleague's advice not to aim for a bulletproof plan. "You do as many reasonable things as you can and accept that."