Staying Positive

Aging with HIV

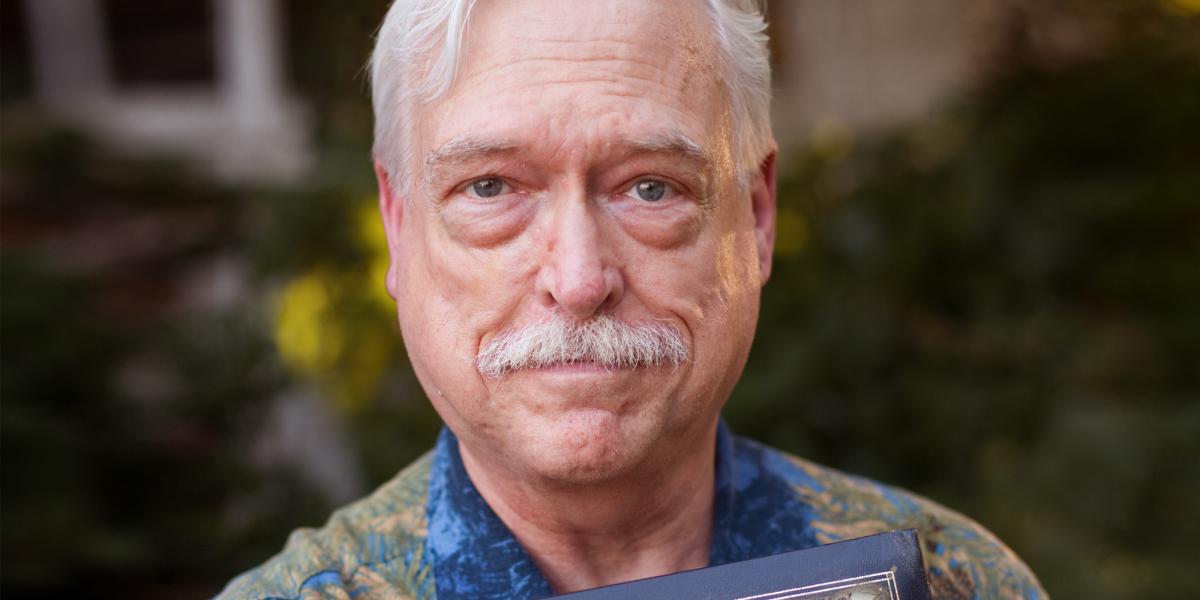

“My partner is 52. I’m 55,” says Chris Camp. “When we’re together, people are constantly saying things to him like, ‘Oh, it’s great that you and your father spend so much time together.’

“And I’m like, ‘I’m not his father.’”

More than 25 years into his battle with HIV and AIDS, Camp is intimately familiar with his war wounds. The constant discomfort, the fatigue. What’s inside is difficult enough to cope with, but as he sits in Baltimore’s Mount Vernon Park on a beautiful late spring morning, the nattily attired Camp is focused on what the world can see of his illness. He’s clearly annoyed at his weathered appearance, the awkward comments, and really, who can blame him?

In one sense, HIV has been kind to Camp: It hasn’t killed him. The same can’t be said for the scores of people in his community who were diagnosed around the same time—1986—as Camp. His address book became a memorial to those men. Unwilling to erase their names and their memories, he chose instead to draw a red line through each lost friend’s entry, annotated with their date of death. In time, page after page became his personal testimony to an epidemic built on suffering.

By the grace of providence and medication, Camp survived. But to say he’s thrived? Even he’s not sure. “I feel like I’ve aged quite rapidly,” says Camp, and at first glance it’s hard to disagree. A tremor in his left hand, deep pouches under his eyes, a head full of snow white, well-kempt hair… he could easily be mistaken for a grandfatherly type by the gaggle of youngsters wandering by on a morning field trip.

What’s happened inside his body since his HIV diagnosis a quarter-century ago is just as debilitating. Three bouts of pancreatitis. Fourteen kidney stones. Diabetes. Triglyceride and lipid issues. Not that Camp, a full-time HIV/AIDS counseling trainer for public health officials, is complaining: Anything but. “Every time I came in to see my doctor for a checkup he’d ask me how I was doing. I’d say, ‘Fine.’ One day he finally said, ‘I want to stop you. Tell me what your “fine” means.’”

So Camp told his doctor his definition of “fine”: Ever-present bloating, nausea, cramping—and lots of understandable worrying. Camp pats his rounded paunch, which seem physiologically at odds with his thin arms and legs. “I have this stone of a stomach, filled with visceral fat that I can’t get rid of,” he says, referring to a common side effect from HIV antiretroviral therapy that redistributes fat away from the limbs and toward the gut. “All of this [visceral] fat is the biggest risk for heart attack and played into my getting diabetes.”

Given Camp’s ongoing battle and the devastating nature of HIV’s history, it’s easy—and somewhat logical—to assume that everyone aging with HIV is facing a day-to-day struggle. But as public health officials are learning, the prognosis for HIV-positive boomers and elders is far more complex—and perhaps for some, far more hopeful—than many might expect.

According to the CDC, by 2015, half of everyone diagnosed with HIV in the U.S. will be 50 or older. In raw numbers, that’s likely to be around 600,000 people. In one sense, this older boom in survivorship is an incredible public health success story.

Consider: Before 1996 and the introduction of drug combinations that suppressed HIV, many people believed that an HIV diagnosis equaled a death sentence, and that they wouldn’t live through their 30s, let alone to 50.

The data backs up that perception. Hopkins epidemiology doctoral student Nikolas Wada, MPH, crunched figures from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), which has been following nearly 7,000 HIV-positive and HIV-negative homosexual and bisexual men at four sites including Johns Hopkins since 1984. Wada found that pre-1996, the median age of death from all causes for the HIV-positive men he observed, using age 35 as a baseline—was only 43 years old—with the vast majority of deaths, 94 percent, coming from AIDS-related causes.

In the real world, that often meant that by the time men were showing any symptoms and finally went to a doctor’s office, their infections had been raging for years, their immune systems effectively destroyed, and their life expectancy at diagnosis a mere year and a half. “In the last three years of the ’80s, I lost 175 friends. It all happened so quickly,” recalls John Crockett, who was diagnosed with HIV in 1987 and thought he’d die within months. “I can remember going to a funeral home in the morning, and going back in the evening to be in the same room with a different body.”

That Crockett is alive today is also reflected in Nik Wada’s data sifting. Post-1996, public health experts say a variety of factors, including new and less toxic medications, faster diagnosis and better clinical management, had greatly lowered the number of HIV deaths directly related to AIDS. Wada’s numbers showed that it had become a statistical tossup as to whether HIV-positive men in the MACS would die from AIDS or non-AIDS related causes. As a result, using his same baseline of 35-year-old infected men, the median age of death from all causes had jumped to more than 57 years of age. A 2009 CDC study confirms this lifespan increase. Looking at HIV surveillance data from 25 states, researchers estimated that as of 2005, people with HIV could now expect to live more than 22 years after diagnosis, and some experts feel the average survival time is even longer.

From a public health perspective, that extended timeline has essentially redefined an epidemic. While people are still getting infected—the CDC’s latest numbers state that more than 56,000 Americans contracted HIV in 2006—“the availability of medications has changed HIV from an acute infectious disease with a high mortality rate to one that behaves like a chronic disease that people can live with,” says epidemiologist Lisa Jacobson, ScD ’95, MS ’86, principal investigator for the MACS Data and Analytical Coordinating Center at the Bloomberg School.

Jacobson is by no means alone in her assessment of HIV management as it is practiced in America, where access to antiretroviral drugs is predictably far greater than in developing countries still ravaged by the disease. All of the more than a dozen Johns Hopkins public health and clinical faculty interviewed for this story, as well as several of their patients who have survived AIDS well into their AARP years, used the phrase “chronic disease” to characterize HIV infection.

But chronic diseases by their very nature cover a wide spectrum of severity. Even within a given chronic disease such as multiple sclerosis, progression and impact on daily life can vary greatly.

Which is why study of the aging HIV population is so important. As HIV-infected people reach their golden years, a host of questions has arisen—including how well will they age, and whether the virus long residing in their bodies makes them more prone to earlier onset of diseases that claim the elderly. “The question is not so much whether you will live as long as your (uninfected) brother but whether you will have more medical problems as an older person than your brother,” says Joel Gallant, MD, MPH, associate director of the Johns Hopkins AIDS Service.

To answer this means delving into a multifaceted puzzle that, on one end, teases apart the lifestyle risk factors particular to certain HIV-infected subgroups. For example, smokers may develop lung cancer or IV drug users may become infected with hepatitis C. HIV and its treatments may negatively affect both. On the puzzle’s other end is investigating HIV’s impact on the aging process itself, and whether the infection, even in a medically suppressed state, promotes premature aging of the immune system. And in between is the ever-moving target of how the timing of the beginning of antiretroviral treatment affects long-term outcomes.

The insights already gleaned have been both surprising and controversial, setting off a vociferous debate among public health researchers as to what recommendations, if any, the data currently support vis-à-vis changing the standards of care for aging HIV patients… patients who fervently hope their best years are still ahead of them.

From nearly the beginning of the AIDS epidemic in 1981, Hopkins epidemiologists have relied on unique cohorts of patients to help them define, control and treat HIV infection. What sets the researchers’ approach apart is that instead of comparing people with HIV to those in the general population—a study practice that, in many epidemiologists’ opinions, leads to misleading results—the epidemiologists have intensely studied HIV-positive and HIV-negative people from the same backgrounds for decades.

In the MACS study, that’s been almost entirely men who have sex with men. The ALIVE study (AIDS-Linked to the Intravenous Experience) has looked at some 4,000 injection drug users in East Baltimore since 1988, while WIHS (the Women’s Interagency HIV Study) has enrolled more than 3,700 women since it began in 1993. In each case, the participants have given greatly of their time and bodies. In the MACS cohort, for example, some people travel several hours to keep their semi-annual commitment.

“I can’t say enough positive things about the participants,” says Jacobson, who helps create statistical models to make sense of the mass of MACS data coming in from sites in Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles and Pittsburgh. “In addition to extensive medical questionnaires and the physical, we have exams to observe things like frailty, so we have them do timed walking and hand gripping. For kidney function we had a subgroup that went through infusions (they had an intravenous solution of Iohexol, which the kidneys normally quickly excrete), and had blood taken five times over four hours. We have another sub-study on cardiovascular disease where a group goes for IV contrast (injection) and cardiovascular scanning.

Not long after being diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1994, Mike Willis nearly died. But since then, he has stabilized on a modest two-drug HAART regimen. “I don’t have a lot to complain about,” he says. “I’ve done really well, and I’m grateful.”

“It’s incredible,” she continues. “We’re learning so much. We just pulled stored blood [from] 12,000 person visits over 25 years, to look at markers of inflammation and co-infections. In the MACS, we have over 600 men who became infected while under observation, who contributed specimens before and after infection, as well as before and after initiation of treatment. So we can see how biomarkers (such as those that can measure presence of heart disease, inflammation and cancer) are affected from both HIV and treatment. They also go through neuropsychological testing so we can see the effects of infection on cognition and memory.”

Given this level of scrutiny, the cohorts have yielded a treasure trove of findings; some 1,100 published papers from MACS, and 365 from ALIVE, according to its PI, epidemiologist Gregory Kirk, MD, PhD ’03, MPH ’95. Historically, those MACS papers helped confirm the mechanism for how HIV replicates and destroys key CD4 immune cells in the process; the relationship between high HIV viral load, low CD4 cell counts and the progression of illness; and the point at which so-called HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) should be started to maximize its effectiveness.

Now those data are being used to determine long-term consequences of HIV infection and treatments on aging. When an April 2011 Journal of the National Cancer Institute paper highlighted the U.S. cancer burden among HIV-infected individuals, it set off alarm bells among many older patients and clinicians, especially when its authors noted, “HIV-infected people are at an increased risk of many non-AIDS defining cancers... In a meta-analysis, these risks were estimated to be increased threefold for lung cancer, 29-fold for anal cancer, fivefold for liver cancer and 11-fold for Hodgkin’s lymphoma.”

Bloomberg School researcher Joseph Margolick, MD, PhD, suggests taking these concerning numbers with a grain of salt. Margolick, who is the PI of the MACS Baltimore site, says many studies attempt to draw conclusions without having cohorts that contain large numbers of HIV-negative and HIV-positive persons from the same at-risk populations. He notes that people at risk for HIV are different from the general public in terms of exposure to many infectious agents. For example, injection drug users have a much higher rate of hepatitis C infection than the general population. So in that case, to assess the effects of HIV infection, it’s important to compare HIV-positive injection drug users to HIV-negative injection drug users rather than the general public, he says.

In the case of MACS, Margolick says the study has yet to confirm which cancers (or other diseases) are caused by sheer aging versus some combination of long-term HIV infection, HAART treatment, co-infections (such as HPV or hepatitis B and C), and lifestyle choices.

Margolick is also a bit dubious of the connection between HIV and so-called “premature aging.” It has been observed that, in people with HIV infection, immune cells appear to break down sooner than in HIV-negative individuals, perhaps because of constant immune system activation. The result is an increase in the type of poorly functioning immune cells that are also seen in HIV-negative people as they age.

“But just because it resembles the way an older immune system looks doesn’t mean the reasons for the changes are the same as in an [uninfected] older person,” says Margolick. “We need to know the mechanism of how you got there. What is the mechanism of age-related changes? And is the mechanism the same for people with HIV? Until we know that, I’m cautious on the whole subject. I just wrote a newsletter to the people in our study where I said, ‘It’s premature to say there’s premature aging.’”

Although the potential differences in the mechanisms of age-related changes in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals are unclear, age-related diseases are becoming a reality for people with HIV. “We see more and more HIV-infected individuals confronting health challenges related to diabetes, bone disease, cardiovascular disease, cancers and other age-related co-morbidities,” says Keri Althoff, PhD ’08, MPH ’05, a Bloomberg School epidemiologist who has worked on the MACS and WIHS studies and specializes in aging with HIV. “Prospective studies are under way to determine if the incidence of these age-related diseases are different than what we observe in individuals who are aging without HIV infection.”

Althoff, an assistant professor in Epidemiology and in the Statistics in Epidemiology (STATEPI) group, has an interesting take on the study cohorts and how to perhaps best predict the risks they face for specific conditions given their current median ages. She notes that while the overall numbers in the cohorts are large, the median age of study participants—54 in MACS, 46 in WIHS—means they aren’t quite old enough to see large numbers of definitive conditions such as heart attacks and diabetes.

“These folks are not as old as [HIV-uninfected] baby boomers, those over 65. So it is likely that the wave of age-related co-morbidities [found in those over 65] is still on the horizon for our cohort participants,” notes Althoff. She suggests that a more robust assessment of risk in the cohorts might come from looking for the subclinical markers of illness and seeing whether they play out equally in the HIV-positive and HIV-negative participants. “Instead of studying diabetes, we can study markers of insulin resistance, which are on the pathway of progression to type 2 diabetes,” she says. ”Instead of studying heart attack, which happens more frequently in the aging general population but is a very rare outcome among our cohorts, we can study precursors for cardiovascular disease such as the thickness of arterial walls, statin use, blood pressure and CRP levels.”

Their findings may change treatment of HIV yet again.

Ask anyone aging with HIV what they’ve been through, and it’s rare to find someone who has come through the infection physiologically unscathed. Some, like Chris Camp, face a non-stop battle: Between serious complications that were part of the often-extreme toxicities inherent in early AZT and HAART treatment, and an ongoing daily regime of dozens of pills to control both his infection and numerous health issues, “there’s not a moment that goes by, living with it as long as I have, that I don’t know that I’m HIV infected, that I have this disease. It’s in my head all the time like a noisy alarm clock,” says Camp, his index finger tapping the center of his forehead for emphasis.

Others, such as 50-year-old Mike Willis, diagnosed in 1994, had extreme early struggles with HIV—various degrees of drug resistance had him, at one point, on a combination of seven different antiretroviral medications that knocked down his viral load, but “my liver, kidneys and pancreas almost shut down,” recalls Willis.

He nearly died as a result, but has long since stabilized on a modest two-drug HAART regimen. A diet and fitness devotee, Willis looks fit as the proverbial fiddle. Once on long-term disability due to his infection, he’s gone back to work and often bikes to the gym for long, energizing workouts. He cheerfully admits, “I don’t have a lot to complain about. I’ve done really well, and I’m grateful,” though he also notes that he’s had to exercise hard to stave off the effects of osteoporosis (he was diagnosed with the bone-loss condition at 43, and it’s since improved), and he takes medication for high cholesterol, both conditions perhaps relating to his HIV status and treatment.

Then there are those for whom HIV has proved more burdensome as the years have gone by.

Marilyn Burnett, 68, contracted HIV in 1991. She has successfully avoided the opportunistic infections associated with her AIDS diagnosis. Her generally good overall health allowed her to become a well-known Baltimore advocate for HIV education, notably with Older Women Embracing Life, an HIV support group run in partnership with Hopkins Medicine’s AIDS Education Center.

Still, certain conditions related to the infection are beginning to concern Burnett. The neuropathy long in her feet, a common drug side effect, is now affecting her legs as well. But most worrying is her memory, which was always razor sharp. Cognitive impairment has long been observed in some HIV-positive patients; Burnett, a self-admitted fanatic about taking her medication on schedule, says, “After 20 years of being very adherent, I’m [now] forgetting to take my medication. And they’re right beside my bed. [But] some days it’s not even on the radar screen,” she says. “A few months ago my pharmacist called me to say, ‘Ms. Burnett, isn’t it time to refill your medication?’ And it hit me, because I had forgotten so often that I had so many pills left in all the bottles that it didn’t occur to me that it was time to call in my renewal. That made my blood turn cold.”

With so many potential co-morbidities to observe and quantify, public health officials are being conservative when it comes to making hard and fast clinical recommendations specifically related to aging HIV patients (though it should be noted that numerous Hopkins clinicians who treat HIV-infected patients say they’re relatively aggressive when it comes to screening for suspected linked conditions, including bone loss, metabolic syndromes, liver disease and kidney function).

Still, researchers have some strong opinions regarding areas of potential therapeutic value to HIV patients. “Smoking has such a high prevalence among populations living with HIV. Depending upon which cohort we look at here, prevalence runs between 60 and 80 percent,” says David Holtgrave, PhD, chair of Health, Behavior and Society. “We’re trying to convince funders to support work that examines the best way to do smoking cessation interventions among persons living with HIV.”

Lisa Jacobson says she’d like to see more clinical emphasis on anal cancer screening. “A lot of literature coming out, including our own, is showing the incidence of anal cancer is much higher in HIV-infected gay men than uninfected men.” Jacobson especially points to screening for co-infections common to certain HIV-positive populations. In addition to doing anal pap smears looking for HPV that can lead to anal cancer, she notes the high vulnerability of HIV-infected IV drug users to HCV (hepatitis C virus) that can lead to liver cancer and other serious hepatic issues.

“It’s clear that HIV fuels the fire of hepatitis C,” agrees Gregory Lucas, MD, PhD, an associate professor in Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “Having HIV and hepatitis C causes liver disease progression that’s on the order of sevenfold faster than in HIV-uninfected people with hepatitis C.”

A few months ago, Marilyn Burnett’s pharmacist called to remind her to refill her medications. “I had forgotten so often that I had so many pills left. It didn’t occur to me to call in my renewal,” she says. “That made my blood turn cold.”

Lucas adds that keeping a close eye on kidney disease, his prime area of study, is equally important. “There’s no question chronic kidney disease is increased with HIV infection and, potentially, its treatments. The order of magnitude in what I’d call well-characterized HIV-positive and HIV-negative populations is threefold to fivefold higher risk, what I’d call unequivocal. In African-Americans in particular, the risk of end-stage kidney disease is increased at least 10-fold with HIV infection.”

But perhaps the strongest recommendations for screening have to do with finding those estimated 21 percent of infected Americans who don’t know they are already HIV-positive, as well as people who don’t perceive themselves to be at risk, notably sexually active elders. The over-50 population is the fastest growing group of those newly infected with HIV. And while drug toxicities have greatly dropped, there’s evidence that the infection is harder to combat in older populations, perhaps because their immune systems have been compromised by age. While the CDC recommends HIV testing up to age 64, John Bartlett, MD, professor of Infectious Diseases at Hopkins Medicine, notes the American College of Physicians suggests upping the age of testing to 75.

One thing is clear: Many sexually active elders are surprised that HIV could possibly affect their lives. Bloomberg School epidemiologist and physician Kelly Gebo says, “I’ve been to several senior centers and [asked], ‘How many people here have had a high-risk HIV behavior?’ and they’ve had no idea. Then I ask, ‘How many people here have had unprotected sex?’ and many of them raise their hand. I then say, ‘Well, all of you have been at risk.’ And they look at me like ‘what, are you crazy? Only reckless young people or drug users get that. Not people who go to my church!’”

Gebo, MD, MPH, an associate professor in Medicine and in Epidemiology, adds that “getting people diagnosed at an older age is often hard because providers and geriatricians may feel less comfortable asking about high-risk behaviors. There’s often a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ principle. I ask everyone between 12 and 112, ‘Are you having sex? Anal, vaginal, or oral? With protection? With men, women, or both?’ When you ask [older] patients this, without judgment, they answer you.”

While the risks for premature aging and certain diseases are still being assessed and debated, graying patients, meanwhile, are doing their best to make life with the infection both long and vital.

“I’m extremely vigilant, and unless an asteroid drops on my head, I think I’ll be around here a long time,” laughs Chris Camp.

“And if I live to be 85, would they say I died of AIDS?”