Death, Reimagined

Imagine living in the 19th century. Now imagine dying.

Death is a frequent visitor. It stalks your family, your neighbors—everyone—especially infants and young children. From your parents, you inherit a kind of fatalism, a resignation to death’s commonness as God’s will.

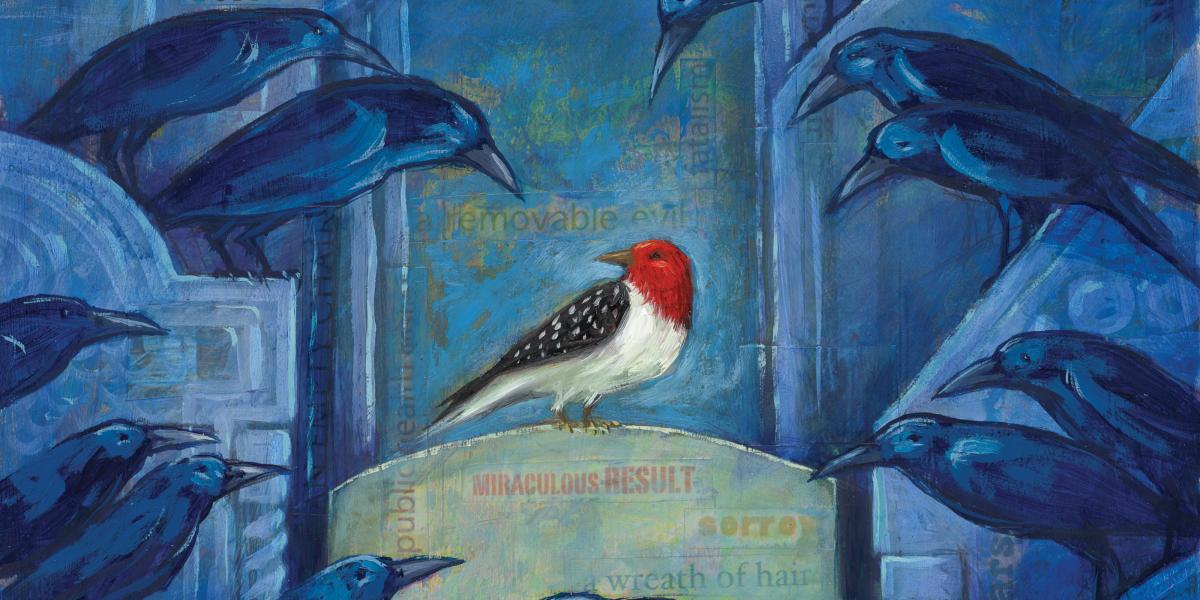

When a family member dies, you prepare the body in your own home. You plan for an elaborate last photograph. You carefully arrange her clothes and hair so she appears to be sleeping. Like many people of your era, you weave a wreath of her hair to keep as a constant reminder. If your child dies, you pay for the gravestone to be adorned with a lamb, a daisy, a vacant chair or other Victorian symbol for children.

By the turn of the century, however, this romantic view of death was about to be swept away.

Change came slowly at first. Public health reformers in the U.S. began to systematically collect statistics on births, deaths and disease. Their data exposed the appalling scope of disease and death. In 1885, one in every four infants born in New York City died before their first birthday. In Atlanta in 1900, an astonishing 45 percent of African-American infants died before age 1. And that year, one in every 500 Americans died of tuberculosis.

At the same time, mass sanitation, modern water and sewer systems, and immunization programs began slashing rates of the deadliest infectious diseases. By the 1920s, vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, typhoid and other diseases had begun to make a difference. The combined result was extraordinary. From 1885 to 1915, New York City cut its infant mortality rate by two-thirds. Such statistics fueled public health efforts to convince the public that disease was preventable, death not inevitable. State health departments sent “health trains” into the countryside extolling the benefits of window screens, hand washing and safe food handling. Lantern slide shows and a circus midway atmosphere attracted crowds eager to hear the gospel of public health.

Reflecting the era’s growing confidence, the great health reformer Hermann Biggs proclaimed in 1911, “Public health is purchasable. Disease is largely a removable evil.”

The public health revolution, while amazing, was far from equitable. People in cities enjoyed nearly twice as great a reduction in mortality as rural residents. Whites in Northern cities benefited most of all. In the South, poverty and the lack of access to health care ensured that diseases like malaria, dysentery, typhoid, influenza and tuberculosis flourished. It would take World War II’s economic boom and government programs by leaders like U.S. Surgeon General Thomas Parran to push Southern mortality rates close to the national average.

Public health’s success in raising life expectancy by 20 years in most Western countries during the first half of the 20th century spurred efforts to extend those gains globally in the century’s second half.

Once again, public health would have to change attitudes toward death to save lives. Carl E. Taylor, later chair of the School’s Department of International Health, argued in The Atlantic in 1952 that adequate family planning would be a boon to maternal and child health. But he knew it wasn’t feasible to work on lowering the birth rate without also addressing the death rate. In India, for example, 45 percent of children died before age 5 in the early 1950s. Until parents could be assured that more of their offspring would survive, they would never accept birth control. This insight became an essential tenet of the child survival revolution, which began in the 1980s and would achieve historic reductions in infant and child mortality.

While public health still has much work to do, death is more of a stranger to us than it was to our ancestors. We can rejoice with public health pioneer Charles V. Chapin who wrote in 1921: “Figures do not measure the terror of epidemics, nor the tears of the mother at her baby’s grave. …To have prevented these not once but a million times justifies our half century of public health work.”