Lions in Winter

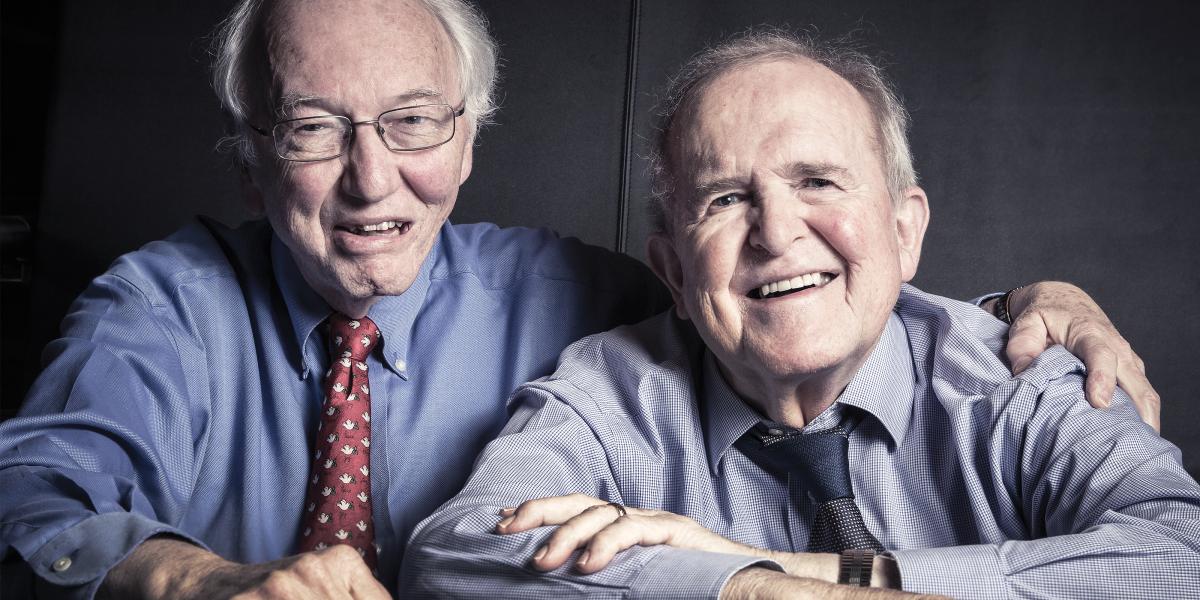

They won’t tell you, but the humble Sack brothers are public health legends.

“What does a cholera outbreak look like?”

With a click of the mouse on his office computer, David Sack answers the question. An Al-Jazeera documentary comes on the screen showing a three-wheeled taxi screeching to a halt outside a hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. In the back seat is a young man, nearly dead, a victim of cholera. The scene is chaotic. The patient is hustled onto a gurney. He has no pulse. His eyes have rolled back in his head. Just hours before, he was healthy. The gurney is run along an alleyway into a cholera ward. Cot after cot is lined up. Each has a hole in its middle to allow diarrhea to empty into buckets. The man is gently laid on one. His condition is so dire that he’s given a special IV solution in the back of both hands. If the taxi had been delayed even 15 minutes, his nurse says, he would be dead. Instead, in a half hour, like Lazarus, the man is awake, dazed but smiling.

The video stops. David Sack turns and says, “During a cholera outbreak, this happens 500 times a day.”

He should know. Both he and his older brother, Brad, have been on the front lines of the cholera wars for a combined 90-plus years. Together they’ve helped save millions of lives, and have helped to turn what was once a death sentence into a fighting chance at life.

By attacking—and in one case discovering—bugs such as Enterotoxigenic E. Coli (ETEC), rotavirus and another bacteria (Vibrio cholerae) that causes cholera, the Sack brothers have become legends in the field of diarrheal disease research and treatment. Their efforts have contributed to cutting infant mortality drastically in developing countries like Bangladesh.

“Both Brad and David Sack have made major contributions in the field of enteric diseases, and vaccines to prevent those diseases,” says Neal Halsey, MD, a Bloomberg School professor with the Johns Hopkins Vaccine Initiative. “They’ve been the cornerstones of our teams dealing with enteric diseases.”

On a recent late winter morning, the brothers are sitting around a table in David’s small office on the fifth floor of the Bloomberg School, where they hold appointments in International Health. A child’s cholera cot sits folded against the back wall, a prop for David’s lectures on the disease. At 79, Brad Sack, MD, ScD ’68, is in a wheelchair, his legs impaired by a neurological condition. He also suffers from macular degeneration, but he remains, with an assistant, committed to reviewing papers and grant proposals on his weekly visits into the office. David Sack, MD, at 71, is still a workhorse, putting in 12-hour days because, in his words, “there’s so much opportunity to do more.”

“I get the feeling that [David] doesn’t want to retire until every last Vibrio cholerae bacterium has written him a personal letter of apology,” says colleague Peter Winch.

Maybe it’s the daunting nature of their work—diarrheal diseases are still the second leading cause of worldwide deaths among children under the age of 5—or more likely it’s their own self-effacing nature, but ask the Sacks what they’ve accomplished in their careers and they’re stumped. Silent.

“Gee, that’s a tough question,” says Brad after nearly a 15-second pause.

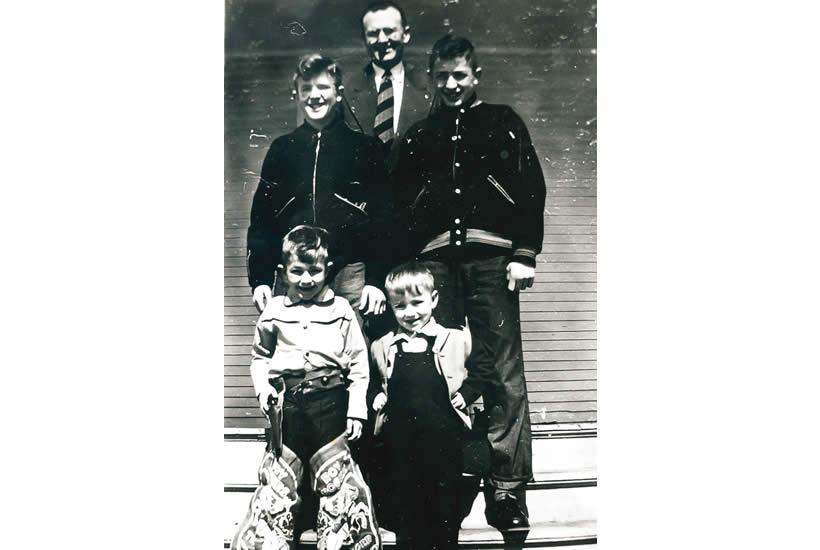

It’s easier for the brothers to reflect on the roots of their humanitarian service. It was ingrained by their father, Noble, a pastor and seminarian in the Evangelical United Brethren Church, and their mother, Wilma, a teacher. Of their father’s sense of service, Brad says, “It was very much in his bones. He was a giver. By what he did and said. He would give himself to students or the congregation, always conscious of relating to people.”

While the Sacks’ only daughter, Kathy, became a nurse-midwife, the Sack boys—Bill, Brad, Bob and David, in age order—all went from Portland’s Lewis and Clark College to the University of Oregon School of Medicine (now Oregon Health and Sciences University). Bill, a renowned child psychiatrist, and Bob, a noted sleep disorders specialist, chose to practice in Oregon, but Brad and David caught the public health bug.

For Brad, it was a seven-week National Institutes of Health scholarship in Guatemala during his senior year of medical school in 1960 that whetted his appetite for infectious disease work. Two years later, he jumped into a two-year Johns Hopkins School of Medicine infectious disease fellowship in Calcutta. His four young children and wife, Josephine, accompanied him, and the environment affected the whole family. “If you took pictures a year after we arrived in Calcutta, we were all skinny and undernourished. We had constant diarrhea when we first came. We all lost weight until we became immune to a lot of the bugs that were there,” says Brad.

Brad saw the worst of it in the city’s Infectious Disease Hospital. There, cholera—a disease so inculcated in the culture that Calcuttans had built a temple to ward it off—was killing half the people who contracted it and didn’t get treatment. Even for those who received the IV treatment of the day—hypertonic saline—the mortality rate was 25 percent. At the time, 1962, Indian doctors treated cholera by withholding water; Brad remembers patients “screaming for water, but the doctors wouldn’t give it to them.”

Brad and a Hopkins School of Medicine colleague, Charles Carpenter, set up a lab and clinic in the hospital. Along with three Hopkins internal medicine residents, they devised an IV solution of sodium chloride to address shock, and sodium lactate to balance out metabolic acidosis. They also had their cholera patients drink green coconut water, which provided potassium chloride. The results were outstanding: Two years, roughly 700 patients treated, zero deaths.

Brad was just getting started. His Calcutta studies would go on to uncover the effectiveness of treating cholera with tetracycline; oral doses would knock out the vibrios in a day, cut stool output in half and reduce the illness duration by nearly half.

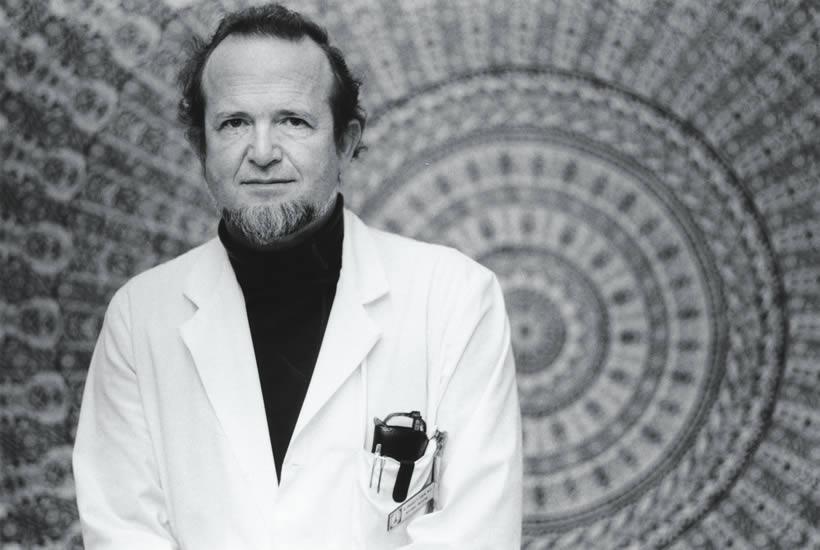

In 1968, after he received his ScD in pathobiology from the then Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, Brad discovered in his Calcutta lab that many cases of presumed cholera were actually caused by another bacterium, ETEC. It turned out that ETEC was the predominant bacterial cause, worldwide, of diarrheal deaths, notably in children in developing countries.

ETEC couldn’t be stopped, but its devastating diarrheal symptoms turned out to be another matter. Brad and Nathaniel Pierce (now Bloomberg School professor emeritus in International Health) were among the first to do a controlled study in children of so-called oral rehydration therapy (ORT).

ORT, which in their version was sodium chloride and glucose, didn’t stop diarrhea, but allowed intestinal absorption of enough sodium and water to maintain fluid balance. ORT turned out to be as effective as IV solutions in moderately dehydrated patients—a monumental breakthrough.

“You have to remember, at the time IV fluids were very expensive, they had to be imported [to developing countries],” says David Sack. “If you had to give 20 to 30 liters of IV fluid to a person [as with ETEC, cholera, or any other diarrheal disease], you can’t distribute that to massive numbers of people.”

At first, Brad says American doctors and leading health organizations were slow to embrace ORT because it originated in India and Bangladesh as opposed to a developed country. But eventually, low-cost ORT was adopted by the WHO as the go-to therapy for cholera and all diarrheal diseases. The therapy, which is delivered undiluted in easy-to-carry salt packages costing 10 cents, today is credited with saving 50 million lives: The Lancet called the discovery of the mechanism behind ORT as “potentially the most important medical advance of [the 20th] century.” And while many other researchers such as David Nalin and Richard Cash, as well as Hopkins’ Nate Pierce, have rightfully received credit for popularizing the use of ORT, “Brad is one of the unsung heroes,” says another ORT pioneer, William Greenough III, a former professor of International Health at the Bloomberg School.

All told, that’s a weighty résumé for a younger brother to aspire to. David Sack had started blazing his own public health trail, directing an Indian Health Center in Lame Deer, Montana, from 1969 to 1971, and subsequently working in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). Still, when he arrived at Hopkins in 1974 as an infectious disease fellow at the School of Medicine, David initially felt like he was operating in his brother’s shadow. “But we eventually became colleagues,” he says.

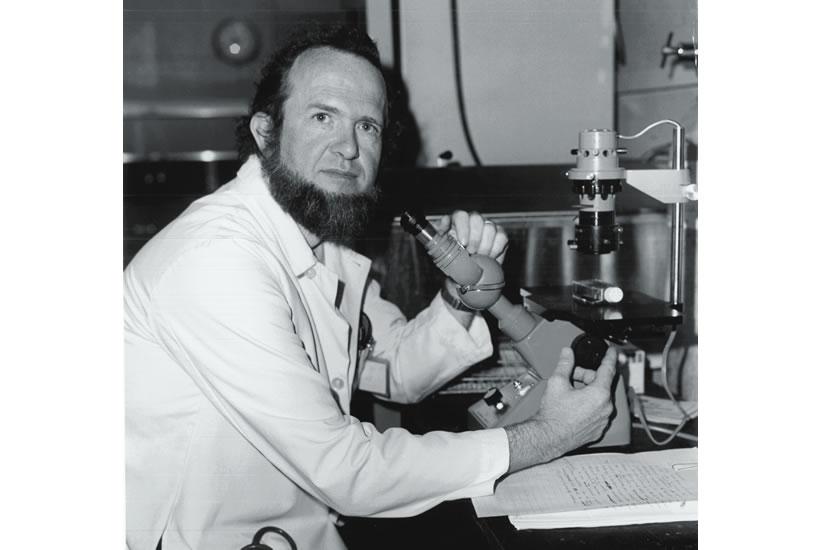

Brad agrees. “I enjoyed the fact that we could talk about the same things. I don’t think we ever felt competitive. We were very supportive of each other.” In fact, David collaborated with Brad on his first five papers; in all, the two have shared credit on 49 papers. They point to their work identifying and treating the causes of traveler’s diarrhea in the late 1970s and early 1980s as a particularly fruitful collaboration. David traveled to Kenya, Nepal, Guatemala and Mexico as part of those studies. But it was in vaccine work that David would make his biggest mark in fighting diarrheal diseases. He ran Hopkins’ Vaccine Testing Unit, which eventually folded into the Bloomberg School’s Center for Immunization Research. His specialty is oral vaccines.

Why oral? “To stimulate the immune system of the intestine, which is different from the systemic immune system,” says David. “Always, in the past, they had been giving vaccines by injection, so they might get good antibodies in the blood, but that’s not where [enteric] disease is.”

The diarrheal vaccines tested at Sack’s lab have greatly reduced infant mortality and diarrheal disease. David’s work on rotavirus played a role in disseminating vaccines that led to huge drops in the disease. A 2011 paper by Bloomberg School colleague Robert Black found that the rotavirus vaccine was responsible for reducing “severe rotavirus episodes” by anywhere from 42.7 percent in high-mortality areas of Asia to 91 percent in developed countries, where the quality of water and sanitation is considerably better.

In addition to being a skilled scientist and epidemiologist, David is also a deft administrator. Over the years he had three tours (and Brad, one) with the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), founded in 1960 as the Pakistan Seato Cholera Research Lab. But when David came back to direct icddr,b in 1999, he found a vital public health organization struggling with financial shortfalls.

Instead of cutting projects, David made the critical decision to grow. “The feeling was, if we cut our budget, we’d become unproductive. Why would anybody want to fund an unproductive institute?” Because of his foresight, the iccdr,b’s work in fighting not just diarrheal disease but HIV, arsenic poisoning and malaria soon caught the eye of the Gates Foundation. In 2001, the center was awarded the first Gates Award for Global Health, a $1 million prize that helped put the institute back on steady footing. “I’m not a salesman,” says David, “but I can talk to donors with credibility.”

That’s a trait both Sacks share in abundance. They’ve also nurtured dozens of careers, with mentees around the world singing their praises. “Both brothers are very humble and easy to approach,” says iccdr,b researcher Wasif Ali Khan, who was referred by David Sack to Hopkins to get his fellowship in clinical pharmacology as well as an MHS in clinical investigation in 2006. “With some high-profile people it’s hard to get an appointment. It’s been very easy with them. And every time David comes to Bangladesh he visits the remote Bandarban field site and meets with the staff, which really encourages them. He brings them chocolates from the U.S. Small things really count for a lot.”

International Health assistant professor Christine Marie George came to the Bloomberg School in 2012, fresh from Columbia University with a PhD, and quickly met the Sack brothers. Through their mentorship, she received three pilot grants and a supplement to their R01 grant, which has since turned into her own career development K01 grant. Under the Sacks' mentorship, George recently conducted a randomized controlled trial of a hospital-based, soap and water handwashing treatment intervention for high-risk families of cholera patients in Dhaka that eliminated all symptomatic cholera infections in this population.

“David and Brad have been wonderful mentors and have given me the opportunity and freedom to go after my intellectual pursuits,” says George. “And it’s through my collaboration with their remarkable research group that we have been able to develop interventions that could help reduce diarrheal disease in susceptible populations in Bangladesh.”

Though Brad’s health has him considering retirement, David remains in the thick of the cholera fight, running the DOVE (Delivering Oral Vaccines Effectively) project. David has long researched cholera vaccine effectiveness; the trick now is figuring out how to best target the estimated 2 million available doses by predicting outbreaks. Here again, the brothers’ teamwork is evident, as Brad’s NIH grant, with a consortium of other universities over the last 16 years, has been identifying the environmental conditions that facilitate cholera outbreaks.

The brothers shyly acknowledge the accomplishments of which they are most proud. “I’d say being able to recognize what organism causes disease, in this case severe diarrheal disease, around the world and to be able to treat it first and then prevent it,” Brad says.

David says, “It’s the comprehensive understanding of cholera: It’s an easy disease to treat, and I think I played a role in that. It’s an easy disease to diagnose, and I think I played a role in that. You put that together with the vaccine, and theoretically we should be able to eliminate cholera as a public health problem.”