At Home on the Reservation

Mathuram Santosham saved his life—and millions of others—by learning to be a “champion of failure.”

Something was different about many of the children at the jam-packed marketplace in Kathmandu, Nepal. They had big, distended stomachs and grisly skin infections. The air of sickness about them was disconcerting, even to a 5-year-old. Flora Wilfred must have noted how Mathuram, the youngest of her three children, was studying the scene around him that day in 1949. She told him: “You must one day become a doctor and help as many of these children as possible.”

Little “Mathu” would do that—and more.

Mathuram Santosham would become a physician, find his way to the U.S. and spend 36 years working with Apache and Navajo Indians. Over the years, he would stop deadly diseases like Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and meningitis by proving the effectiveness of vaccines and treatments. His advances would spread worldwide to mind-boggling effect:

- Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) treatment for diarrhea has saved an estimated 50 million lives. Santosham conducted a key field trial on the White Mountain Apache Reservation in Arizona that proved its effectiveness to a skeptical medical community. His studies also helped demonstrate that infants would get better faster if they ate food during their illness, overturning a then-common practice in diarrheal care.

- Santosham was one of the first researchers to demonstrate the effectiveness of a vaccine against Hib that is now used around the world. By 2020, it will have saved an estimated 1.5 million lives.

Santosham, who stepped down on April 30 after 25 years as the founding director of the Center for American Indian Health at the Bloomberg School, was awarded the 2014 Fries Prize in honor of his accomplishments. The prize is awarded to “the individual who has done the most to improve health” around the world.

When health care entrepreneur James Fries introduced Santosham at the award ceremony, he ticked off those astonishing numbers of lives saved by Santosham’s work.

That work is “not just about discovery,” Fries said. “Mathu also takes his discoveries out into the field. He does that in places where diseases are thriving and entrenched, where there is lots of poverty and lots of other problems. He gets his work to the stage we call upscaling, where it goes from helping the few to helping the many.”

When Santosham stepped up to the dais to accept the prize, he wore a dark suit and tie. And while his remarks included thank-yous and war stories, his central message surprised many.

“I am going to tell you in the next few minutes mainly about my failures in life,” he began. “A lot of people talk about their successes in life, but if anyone has learned over the years to become a champion of failure, it’s me.”

A SECOND CHANCE

The story of the first of Santosham’s failures begins in Nepal, the site of the first assignment with the Indian diplomatic service for family patriarch John Wilfred Santosham, who worked under the more Anglo-friendly name of S.J. Wilfred. In Kathmandu, the family learned that the city had no viable schooling options for the children of diplomats.

Flora and John sent the older two children back to family in India, but Mathu stayed in Kathmandu. He didn’t enter a proper classroom back home in India until the age of eight. When his father’s career took the family to Germany four years later, Mathu and his older brother landed in a boarding school in Glasgow, Scotland. Santosham shivers to this day at the memory of life there without central heat or running hot water.

The Scottish school system in those days administered an exam to 12-year-olds that pretty much determined a child’s future. Santosham failed that test. Soon after, he found himself in front of the headmaster, who asked Mathu what he wanted to be when he grew up.

“I want to be a doctor,” Santosham said.

“That’s not possible anymore,” the headmaster replied.

The headmaster started talking up life as an auto mechanic. Santosham started to cry. Then a teacher, Miss Grant, interrupted, asking Santosham to leave the room. From outside, Santosham could hear the two adults arguing. When Miss Grant emerged, she announced that he would get a second chance at the test.

“There is one condition,” she added. “You have to come in early every morning. You have to stay in at lunch. You have to stay after school. I’m going to coach you.”

Santosham remembers Miss Grant as a teacher whose whole life seemed to revolve around her students.

“What she did for me, she didn’t get a penny for that,” he says. “I think about it sometimes. If she did that for me, how many others did she do it for? And then I think about how I’ve been able to help a few people with the work I do—what about all the other students Miss Grant helped? How many people have they helped?”

THE RIGHT ATTITUDE

The chapter in life that brought Santosham to Maryland began not in failure, but in family tragedy. He was a student at the Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research in the Indian city of Pondicherry in 1969 when a telegram arrived: “Mother expired on July 16. Love, Dad.” Flora had suffered a massive stroke while she and John were visiting a brother of hers who lived in Randallstown, near Baltimore.

After earning his MD in 1970, Santosham found himself drawn to the place where his mother was buried. He and his wife, Patsy, whom he met in medical school, moved to Baltimore so that Santosham could enroll in a training program at Church Home Hospital, then at the corner of Broadway and Fayette streets. The program was a disappointment.

“They were just using foreign medical graduates to do their scutwork,” Santosham says.

He eventually found his way into a pediatrics program at City Hospital, the then-independent predecessor to the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. There, Santosham fell in with a pair of mentors, Harold Harrison and Bradley Sack, who had been involved in the initial development of oral rehydration therapy for diarrhea. One day in 1979, Sack asked Santosham if he had any interest in going back to India to work on a diarrhea study.

“When I heard that, it was like everything was turning out perfect,” Santosham says.

Few failures in medicine are as excruciating as the death of a child, something Santosham learned firsthand in India during a medical school rotation in pediatrics.

“I will never forget the diarrhea ward,” he says. “It was just a kid dying here and a kid dying there and another one dying across the room. The kids were all dying. Their moms were pulling me by the shirt, screaming and asking for my attention to save their child.”

Now, Santosham was in position to go back home and live up to the vision for his future that his late mother had shared in the market in Kathmandu. He, Patsy and their two young children were packing for the trip when war broke out between India and Pakistan. The diarrhea study was canceled.

Scrambling on behalf of his devastated protégé, Sack found Santosham a one-year assignment in another diarrhea study, this one on the White Mountain Apache Reservation in a remote corner of Arizona. On his first trip there, Santosham got lost. He was standing outside his car in the dead of night, trying to decipher a map in the glare of his headlights, when a tarantula crossed at his feet. In his mind’s eye, he saw a hundred rattlesnakes out in the darkness.

He never imagined that in the years to come, he would share the story of that trip to the reservation—and how it came about—over and over again, whenever he was looking to help students and trainees grapple with career setbacks.

“I always tell them that your biggest disappointments in life can turn into some of your greatest assets if you take the right attitude,” he says.

EMBEDDED IN THE TRIBE

The Navajo and Apache reservations where Santosham set out to make a difference were places of extreme poverty where infectious diseases wreaked havoc on par with the poorest countries. Diarrheal diseases, to cite just one example, were killing infants at rates seven times the national average.

When 8-year-old Novalene Goklish met the new doctor on the White Mountain reservation in 1980, Santosham was behind the wheel of a battered old school bus, going from house to house to pick up children for the Sunday school class he taught at Open Bible Lutheran Church.

“The message in Sunday school always had a positive angle to it,” recalls Goklish, who is now a senior program coordinator with the Center for American Indian Health. “Dr. Santosham would always emphasize what the scripture that day meant for how we should treat one another. He was always trying to make sure we looked for the good in people.”

When people involved with the Center for American Indian Health look back at how it came to be such a success, small moments like that loom surprisingly large.

“Mathu really embedded himself in that community from the start,” says Allison Barlow, PhD, who served as the Center’s associate director under Santosham and is now its director. “It wasn’t all part of a big plan. He just did what came naturally.”

For Santosham, work was not a 9-to-5 affair. From day one, he involved himself in community affairs and tried to help out wherever he could. He and his family moved into a home behind the hospital on the reservation. Their children went to reservation schools. Patsy used her skills as an anesthesiologist to help Santosham care for children in the emergency room.

Tribal leaders took a wait-and-see attitude about the new doctor. Their skepticism was based on experience.

“We have a history of people using us as guinea pigs,” says Ronnie Lupe, then and now the chair of the White Mountain tribe.

When Santosham took his diarrhea project to the tribal council for approval, Lupe confronted him about that history: “Doc, are you going to take advantage of us like all of the white guys before you did?”

“Mr. Chairman,” Santosham replied, “if Columbus had known his geography, I’d be living on a reservation in India today and you’d be studying me.”

“One thing about Native peoples is that they have really good instincts about people,” Barlow says. “I think they understood that Mathu was for real. The relationships and friendships he built up on the reservation—all of us working at the Center today are still standing on his shoulders.”

The family lived in Arizona full time for six years. Ever since, Santosham has been shuttling between there and Baltimore on a regular basis.

THE FIRST TRIAL

Oral rehydration therapy is just what it sounds like, a fluid-replacement strategy that keeps patients safe from life-threatening dehydration. Santosham’s mentor, Bradley Sack, was among the researchers who first demonstrated the success of ORT in early overseas trials, but U.S. pediatricians doubted the treatment’s effectiveness. They communicated those doubts to colleagues in foreign countries and foreign-born medical students and trainees at U.S. schools, slowing the acceptance of ORT around the world.

Two things had gone wrong in ORT’s early incarnations. In a well-intentioned effort to make the medicine taste better, the formula used to make it in a powdered form that would then be mixed with water had been altered with sweetening agents that actually worsened a patient’s diarrhea. The second problem was compliance—too many parents put more than the recommended amount of oral rehydration solution powder in the fluid, which actually increased the risk of death by causing a complication called hypernatremia, which involves too much salt in the blood.

Santosham brought the mix of ingredients back to square one and assembled a network of Native outreach workers to help parents stick with the recommended dosing.

The first of a series of trials began in 1980, and the papers that soon followed are now regarded as landmark affairs. One showed that ORT prevented deaths among hospitalized children. Another proved that administration of ORT at home kept children out of the hospital. This was the birth of the now-ubiquitous diarrhea treatment known as Pedialyte.

“People were skeptical about our work at first,” Santosham says. “They would say that this is a unique population, that we can’t be sure the findings are going to apply to the general population. My argument was always that if we can show that this helps people on the reservation, where there is so much poverty and where people are so spread out, then it will probably help people in other places, too.”

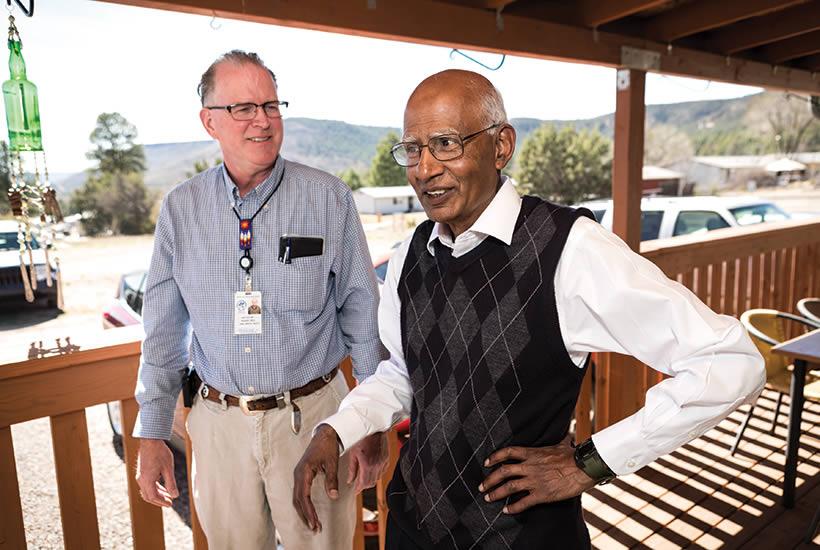

ORT is now listed by WHO among essential medicines that need to be available in every community. While success on a global scale is a testament to Santosham’s acumen as a clinician and researcher, the Navajo physician Phillip Smith of Tuba City, Arizona, sees it also as a testament to Santosham’s work on the local scale.

“The principal reason I think the Center for American Indian Health at Johns Hopkins has been a success is one word: trust,” Smith says. “The Johns Hopkins people were trustworthy.”

While he was working on the ORT trials in the early 1980s, Santosham came across five cases of meningitis, which translated to a prevalence on the reservation nearly 50 times the national average. The culprit was Haemophilus influenzae type B, or Hib, a bacterial infection that can also cause pneumonia and other problems.

When Santosham took this issue before the tribal council, he learned that just about everyone on the reservation knew children who were blind, deaf, paralyzed or dead from meningitis.

“Have you ever tried to do something about it?” Santosham asked.

Santosham doesn’t recall which council member replied, but he remembers the words: “You’re from Johns Hopkins—tell us what to do.”

HIS BIGGEST AMBITION

Santosham’s search for a Hib vaccine that would work in young children stretched out over most of a decade. His first solid prospect came through a researcher who was testing the use of hyperimmune globulin extracted from the blood of healthy immunized patients. It worked, but the cost of $100 a dose was too steep.

Santosham then conducted preliminary tests on four different vaccine candidates before choosing as his next target the one that seemed in preliminary tests to deliver the best protection for babies younger than 6 months old.

“The trial was phenomenally successful,” Santosham says. “It was 100 percent efficacious.” Today, Hib vaccinations are routine affairs for infants around the world.

Santosham and his colleagues at the Center led successful efforts to validate two more vaccines in the 1990s, one for rotavirus disease and another for pneumococcal disease. Along the way, the skepticism that tribal leaders once harbored about this new doctor gave way to confidence.

It was the tribal council that approached Santosham in 1990 about the need to tackle health problems tied to behavioral issues—rates of obesity, diabetes, substance abuse and suicide on the reservation are all well above national averages. Santosham sought advice from then Dean D.A. Henderson, MD, MPH ’60, and the chair of International Health, Robert Black, MD, MPH. They recommended that he start the Center for American Indian Health, which was launched in 1991.

Allison Barlow was among his first hires. Another early addition was Novalene Goklish, Santosham’s former Sunday school student. She helped pioneer and now oversees an array of programs targeting behavioral and mental health issues. She and other Native American staff act as ambassadors for the Center in tribal communities and work to ensure that the Center’s work is culturally appropriate and that tribes feel a sense of ownership about Center initiatives.

Suicide prevention was one early target in this turn toward a new focus. In 1993, a spate of suicides among Apache youths spurred Santosham and Barlow to seek expert help from every corner of the Johns Hopkins system, including Dr. John Walkup, then an assistant professor in the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the School of Medicine. Walkup worked with Barlow, Goklish and the Center to help the tribe set up the nation’s first-ever community surveillance system for suicide. The tribe enacted a law requiring that tribal members and agencies report all suicidal behavior to a central registry. A Center-trained team of community health workers follows up on those reports, connecting families in need with counseling and other services.

“Developing a response to suicide is really what launched our whole behavioral health arm,” Barlow says. “One of the things we have learned is that this tribe can be very innovative in their thinking and, as a sovereign nation, can find creative ways to put bold public health ideas into action.”

Today, the Center operates programs that target diet, self-esteem and parenting skills and rely on community health workers (see sidebar). The Center has also launched a 500 Scholars Initiative that supports educational undertakings by Native Americans and aims to develop the next generation of leaders in public health and other specialties.

“My biggest ambition is to build capacity among the young American Indians,” Santosham says. “I want to see them become leaders not only in their communities but also around the United States.”

“LOOK UP”

As he steps down as director of the Center, Santosham finds his career coming full circle. He wants to spend more time on the global stage, especially on efforts to promote the global use of vaccines against the diarrhea-causing rotavirus.

When Santosham started his work on ORT, diarrhea was killing an estimated 5 million children a year worldwide. That number is down to about 600,000 today—a triumph, yes, but one that remains incomplete. Santosham’s native India is one place where more widespread vaccine use still has the potential to save hundreds of thousands of lives.

When Santosham arrived on the reservation in 1980, he felt a sense of déjà vu about the deadly diarrhea cases that he found there. He had experienced similar heartbreaking scenes during his rotation through the diarrhea ward back in India during medical school.

Today, he recalls his early days in Arizona as “that year when all the kids were just dying.” The bodies piled up, one child after another, no end in sight. There were days when Santosham struggled mightily in the face of all those failures.

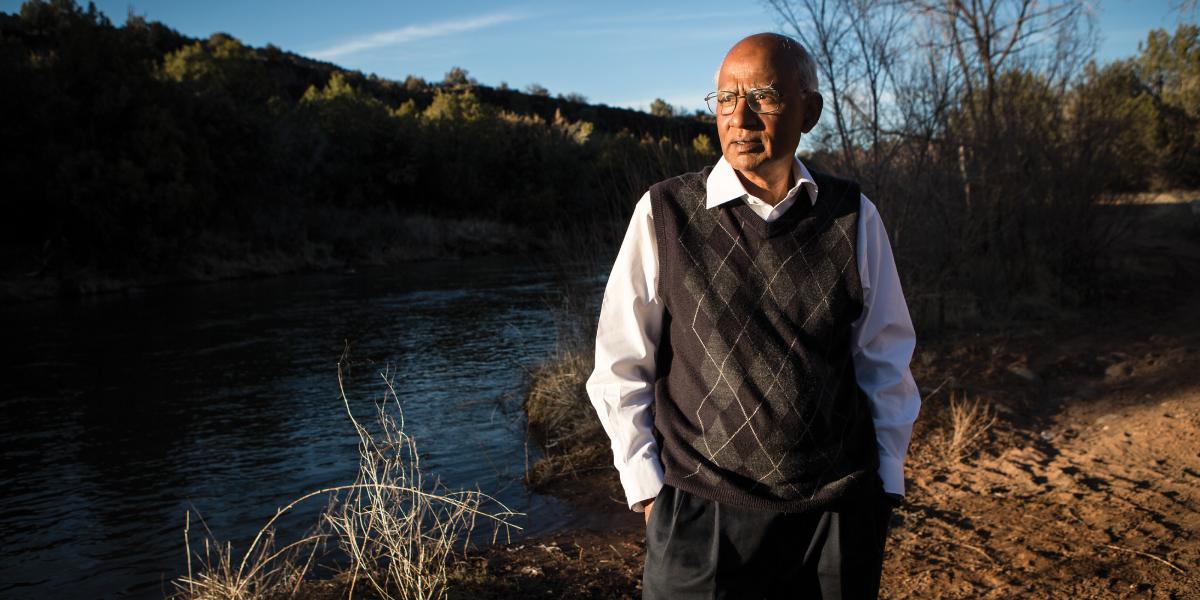

On one of those days, Santosham retreated to an isolated spot along a riverbank near the Whiteriver hospital, looking to spend some time alone. An elderly Native American man stood nearby, fishing. The man started a conversation without taking his eyes off of his fishing line.

“Work at hospital?”

“Yeah.”

“Baby die?”

“Yeah.”

The old man’s gaze remained locked on his fishing line.

“Look up.”

Santosham turned his head to the skies. A raptor soared overhead. It might have been an eagle, but it was hard to tell for sure.

“He’ll take care of you.”

The story is important to Santosham. He wants people to understand that his experiences with Native Americans have been a two-way affair. If he was able to help the tribe discover and develop new ways to deal with health problems on the reservation, they in turn taught him about compassion, resilience and the role faith can play in helping a man find his way through the inevitable failures in life.

“That old man never once looked at me,” Santosham says. “And he had only those few words to say. But he had his way of communicating, and it was very effective if you allowed yourself to be open to it. All I could say to him after that was, ‘Thank you.’”