The Deciding Decade for Infectious Diseases

Two very different threats surged to prominence in the 1980s, remaking public health priorities—and the Bloomberg School.

When Stephen King’s novel The Stand hit bookstores in 1978, its plot seemed completely fantastical: a rapidly mutating strain of weaponized influenza wipes out all but a naturally immune remnant of the world’s population. Yet applicants to the School began citing it in their essays as the catalyst for their interest in public health. Once on campus, however, students found that most of the wet labs—sites of the mid-century triumphs against tuberculosis, polio, and influenza—were long gone. In their place were rooms full of computer terminals and IBM 4331 mainframes used for analyzing voluminous datasets from chronic disease cohort studies.

By then, the terror of past epidemics—like the 1950 polio outbreak that all but shuttered some towns—had faded from Americans’ memories. Public health departments struggled to protect their infectious disease control budgets. Chronic disease in adults claimed the medical establishment’s attention and funding: In 1980, the National Cancer Institute’s budget was five times that of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The main reason Americans let down their guard against infectious diseases was that their children stopped dying. By the 1980s, deaths from microbial and parasitic diseases of extreme poverty had been virtually eliminated in the U.S. Infectious disease case rates were at historic lows. From 1915 to 1989, U.S. infant mortality dropped by 90%. The leading causes—acute respiratory and gastrointestinal infections—had been arrested by antibiotics, vaccines, environmental sanitation, and improved access to medical care, alongside dramatic improvements in household income and living standards.

Yet two very different threats—one striking the developing world’s children and the other slaying young American adults—would shatter Western countries’ complacency toward infectious diseases during the 1980s.

When the first AIDS cases were reported to the CDC in 1981, the pursuit of individual freedom and sexual expression was peaking—wearing a condom seemed archaic to many. At the same time, the public health machinery for responding to sudden, deadly epidemics was rusty.

Early in the AIDS crisis, hospital personnel who feared infection refused to enter AIDS patients’ hospital rooms. With no blood test until 1985, no one knew who had the disease until they developed symptoms. And HIV’s long incubation period of up to 10 years, combined with the intense social stigma against AIDS patients, undercut case-finding and prevention efforts. (The School contributed critical research on all these issues and more through the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, the world's longest study of its kind.) Within a decade of its emergence, HIV would infect more than 1 million and cause more than 100,000 deaths.

If AIDS was a sudden shock with few answers, child mortality in LMICs was a long-burning problem that finally had workable solutions. While wealthy countries had dramatically reduced child mortality, 14.5% of children in low- and middle-income countries were still dying before age 5—similar to U.S. child mortality in 1925. WHO estimated that three-quarters of these deaths in 1985 were from preventable causes: diarrheal disease, acute respiratory infections, malaria, measles, and malnutrition.

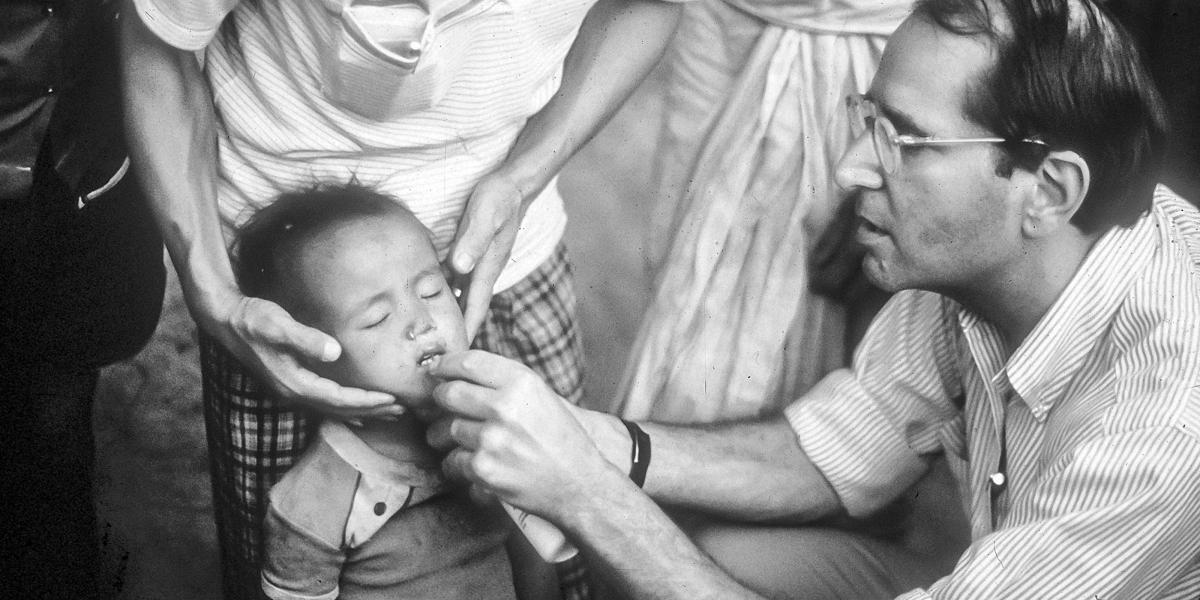

Between 1965 and 1985, current and future School faculty contributed to the WHO campaigns against cholera, smallpox, and malaria and helped to develop oral rehydration therapy for diarrheal disease. Many had started their public health careers in the CDC Epidemic Intelligence Service alongside future Dean D.A. Henderson, MD, MPH ’60, who also led the WHO smallpox eradication program. Others had worked with Carl Taylor, MD, DrPH, founding chair of International Health and director of the landmark Narangwal Study in northern India. The seven-year clinical trial of primary health care interventions among 35,000 villagers demonstrated that child mortality could be cut by up to 45%.

The decade that remade the battle against infectious diseases and child mortality also reenergized the School’s infectious disease research in basic science, epidemiology, and vaccine development and evaluation.

In 1982, UNICEF executive director James P. Grant proclaimed a “child survival revolution” to launch broad-gauged programs combining growth monitoring, ORT, breastfeeding promotion, and immunization (a strategy shortened to the acronym “GOBI”). In 1985, another future dean, Alfred Sommer, MD, MHS ’73, and Keith West, DrPH ’86, MPH ’79, demonstrated that oral vitamin A prevented blindness and reduced child mortality by 33% by strengthening immunity. With the evidence mounting that childhood infectious disease mortality in LMICs could be reduced to the level in industrialized countries, the U.S. government ramped up child survival funding. UNICEF, WHO, and USAID, in concert with national health ministries and private philanthropies, led the global interventions that contributed to a 58% drop in the global under-5 mortality rate between 1990 and 2017.

AIDS likewise elevated infectious disease to the top of the public health agenda. While only five FDA-approved antivirals existed in 1980, more than 40 anti-HIV drugs and drug combinations are available today. The urgent search for AIDS drugs and vaccines streamlined the FDA approval process, beginning with the first AIDS drug, AZT, in 1989, followed by antiretroviral therapy (ART) in 1996. By 2005, the funding gap between NIAID and NCI had nearly disappeared—emphasizing the prioritization of infectious disease.

Compared to AIDS-fighting efforts, child survival programs benefited from more initial consensus on solutions and greater political will to implement them. But global AIDS funding rapidly eclipsed that for child survival after 2003, when President George W. Bush created the President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief. That program delivered ART to countries with high infection rates, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, and saved an estimated 25 million lives.

The decade that remade the battle against infectious diseases and child mortality also reenergized the School’s infectious disease research in basic science, epidemiology, and vaccine development and evaluation. Thirty-nine years after the first AIDS cases were reported, these pivotal investments equipped the School to respond to another novel, lethal, rapidly mutating virus: COVID-19.

-

1982

CDC first uses the term “AIDS” (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome)

-

1989

FDA approves AZT after successful demands by AIDS activist groups

-

1990

130 million infants are being immunized annually, preventing at least 3 million deaths

-

1990

The School’s Center for Immunization Research is the leading U.S. center for phase 1 and 2 vaccine trials

-

2004

Global AIDS deaths per year peak at nearly 2 million