Peter Agre’s Third Act

How a humble Nobel laureate found a new mission: science diplomacy.

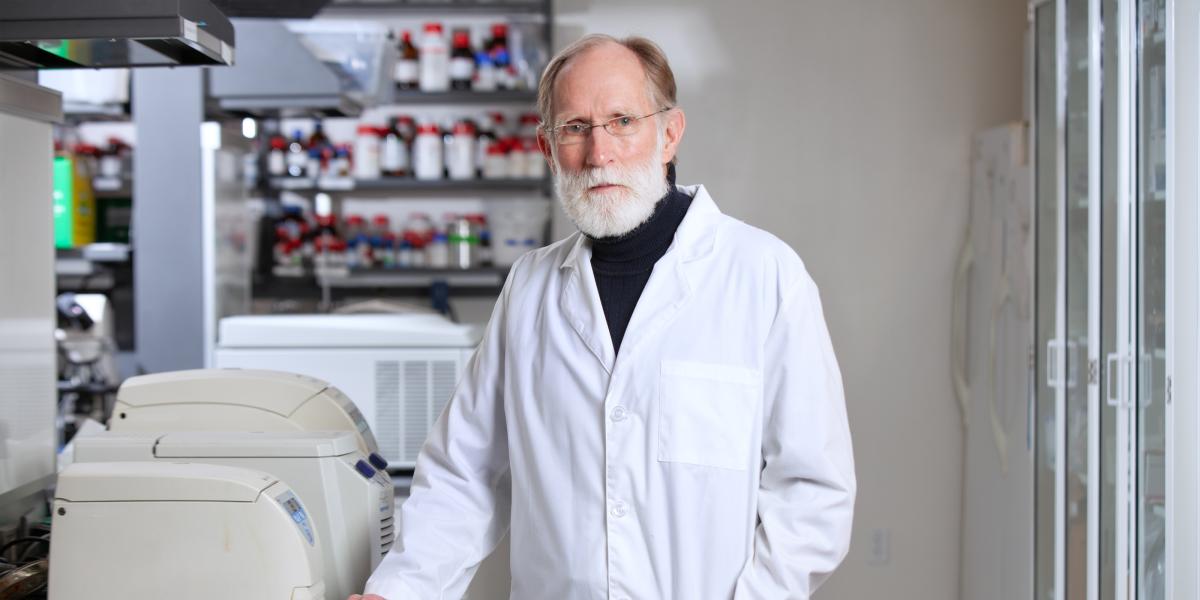

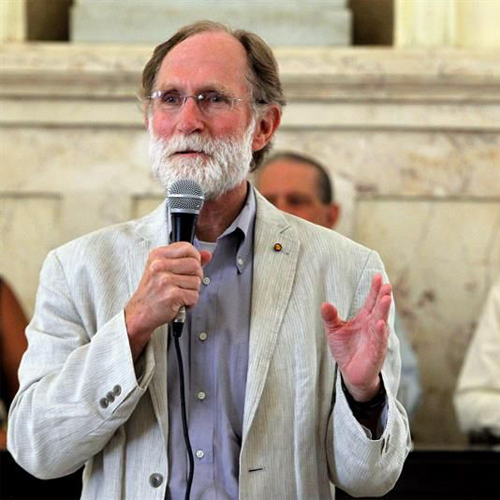

It’s a gray February afternoon in Washington, D.C., and Peter Agre—Nobel laureate in Chemistry, emeritus director of the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute, and staunch advocate for science diplomacy—is patiently waiting to introduce an expert panel on cybersecurity, technology, and diplomacy convened by the Johns Hopkins Science Policy and Diplomacy Group.

Agre has no formal position in the student-run organization, nor is he a panelist. It is even possible, given his near-pathological modesty, that the people milling around the glass-walled conference room at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center, do not fully appreciate who he is. Clad in an old pair of brown corduroy pants and a tie emblazoned with a map of Antarctica, he could easily be mistaken for a random policy wonk.

Not that Agre seems to care. “He’s very humble,” says William Moss, a deputy director of the JHMRI.

Nonetheless, his record speaks for itself. Over the past decade and a half, Agre has led groundbreaking scientific delegations to Cuba, North Korea, Burma (Myanmar), and Iran. He has dined with Fidel Castro in Havana, taken morning tea with former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in Tehran, and serenaded members of the State Academy of Sciences in Pyongyang with Tom Lehrer’s “The Elements” (a recitation of the periodic table set to the tune of Gilbert and Sullivan’s “Major-General’s Song”)—all in the interest of improving human lives and international relations through peaceful scientific engagement.

At the moment, however, he is doing his best to encourage the next generation of science diplomats.

“I’m here to cheer you on!” he tells the student moderator of the panel before turning his attention to the audience. “Science diplomacy is an important part of science, and an important part of diplomacy,” he says, the dome of the U.S. Capitol visible through the window behind him.

On the surface at least, Agre might seem an unlikely candidate for the role of roving science ambassador. After earning his medical degree at Hopkins in 1974 and studying red blood cell disorders, he spent much of the 1980s and ’90s in his lab establishing the existence of aquaporins, a class of proteins that allow water to pass through cell membranes and are therefore essential to life. That discovery earned him the Nobel in 2003, which he shared with Roderick MacKinnon, a Rockefeller University researcher who discovered the structure of another group of membrane proteins called ion channels.

Not long afterward, Agre became vice chancellor for science and technology at Duke University Medical Center. He returned to Hopkins in 2008 to lead the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute, where he investigated the relationship between aquaporins and malaria and vastly expanded the Institute’s presence in Africa through the NIH-funded International Centers of Excellence in Malaria Research (ICEMR) program.

Tackling malaria was something that Agre had wanted to do for decades: It is, he points out, the most severe disease of red blood cells, as well as a crushing global health burden. The WHO estimates that there were 249 million cases and 608,000 malaria deaths in 85 countries in 2022.

“I hate to put different aspects of my career in competition with each other, but the directorship and the work in Africa was a very special part of it,” says Agre, who stepped down as director in 2023. (The JHMRI is now led by malaria researcher Jane Carlton, PhD.)

There seemed little reason, however, to suspect that a late-career tilt toward science diplomacy was in the cards.

Yet Agre’s friends and colleagues agree that it was nonetheless perfectly consistent with his character and values; less a lark, as he self-deprecatingly describes it, and more an expression of his belief in the power of science to benefit the world.

“What changed was not Peter’s interests so much as the opportunities that became available to express [them],” says Landon King, who spent 10 years in Agre’s lab and is now executive vice dean for the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. “He was in the pantheon of science, and it provided Peter with opportunities to do these things that he thought were really important.”

Or as Agre himself told his audience in Washington, “Science opens doors—for the good of all humanity, and the good of our planet.”

Science and technology have long been used as diplomatic tools. Even at the height of the Cold War, American and Soviet scientists and engineers cooperated on projects such as joint space programs and environmental protection initiatives that helped their nations maintain lines of communication.

For much of the 20th century, the principal aim of science diplomacy was to defuse tensions between superpowers and prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons. As the 21st century dawned, however, scientists and diplomats shifted their attention to other urgent global issues such as climate change, sustainability, and food security.

Agre first became engaged in science diplomacy when he was elected president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in 2009. The organization had recently launched a new Center for Science Diplomacy with the express goal of “using science and scientific cooperation to promote international understanding and prosperity.”

The Center aimed to strengthen ties with countries where official relationships either didn’t exist or were highly strained. Its leaders hoped to ease tensions while materially benefiting the populations of these target nations, which often suffered under international sanctions and embargoes.

This, Agre says, is what distinguishes science diplomacy from other forms of international outreach, like cultural diplomacy involving artists and athletes: When scientists collaborate, they can improve the health and well-being of large numbers of people, “sometimes in a permanent way.”

Consequently, when the Center approached Agre about the prospect of traveling the globe to promote collaboration on peaceful scientific projects, he leapt at the chance.

In a sense, he’d been waiting for such an opportunity his entire life.

Agre’s father was a chemistry professor at Lutheran-affiliated colleges in Minnesota, and from an early age Agre was aware of medical missionaries who journeyed abroad to places like West Africa and South Asia.

He also found a role model in the two-time Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling, who used his celebrity as a chemist to lobby against the nuclear arms race. Agre’s father knew Pauling professionally, and invited him to stay at the Agre home in the early 1960s while he gave lectures at local colleges on chemistry, biology, and the dangers of thermonuclear war.

“He definitely was a hero, and still is,” says Agre, who keeps a photo of Pauling, inscribed to his father, in his office.

A summer trip to the Soviet Union in 1966 further whetted Agre’s appetite for travel and his interest in world affairs, and he decided to pursue a career in medicine in part because of the international opportunities it would afford.

When it came time to attend medical school, the presence at Johns Hopkins of what was then known as the School of Hygiene and Public Health was a major attraction. By the time he arrived on campus in 1970, Agre had already visited the School’s Narangwal Rural Health Research Centre in Punjab while traveling solo across Asia for several months after finishing college.

As a medical student and postdoctoral fellow, Agre conducted research on the cholera toxin with faculty members who did work at the School’s cholera research station in Calcutta. When he left Hopkins to pursue further medical training at Case Western Reserve University Hospitals in Cleveland, he thought he knew where his future lay.

“At that point, my ticket was punched,” says Agre, who intended to research infectious diseases in developing countries.

A plan to work on cholera in Ethiopia as part of a new program in global medicine fell through, however, when Agre’s wife, Mary, became pregnant; and after completing a clinical fellowship in hematology and oncology at the University of North Carolina, Agre returned to Hopkins for further postdoctoral work. In 1983, he secured a position in the School of Medicine and a small lab at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Agre had by then developed an interest in red blood cell disorders and was attempting to isolate a particular red cell protein when he discovered a second, unidentified protein in his sample. That protein, which Agre wryly refers to as “the contaminant,” turned out to be aquaporin—the first known membrane water channel.

“It took some doing to figure out what it was,” says Agre, who assembled an international team of collaborators to investigate aquaporin’s structure and function.

As interest in aquaporin began to build, Agre found himself once again traveling the world, this time as a lecturer. He especially enjoyed meeting with and encouraging young scientists, a trait he may have inherited from his father.

“His students were his life,” Agre says. “Teaching the next generation seemed like an honorable tradition.” When Agre was asked to make a speech at the Nobel laureates’ dinner in Stockholm, he used his time to promote science education for young children. (When asked about that speech, Agre characteristically deflects attention from himself by shifting the focus to Mary, who taught preschool. “Her 3-year-old students and my 26-year-old graduate students had a lot in common,” he says, “although her students bit each other and peed their pants more often.”)

If science education and advocacy were high on Agre’s list of priorities, so were human rights: From 2005 to 2007, he chaired the Committee on Human Rights at the National Academies of Sciences, which helps secure the release of persecuted scientists, engineers, and health professionals around the world; and one of his first acts as president of the AAAS was to launch a Science and Human Rights Coalition. “He had a very strong set of social justice sensibilities,” says King.

He also had a strong interest in politics—so strong that he seriously considered running for Minnesota’s open Senate seat in 2007, going so far as to consult with pollsters and national political figures before ultimately deciding against it.

Agre looks back on this period of seemingly divergent activities with mild bemusement. “I was having attention deficit difficulties,” he says. The unifying thread, however, was Agre’s desire to use the cachet conferred by his Nobel to effect positive change in the world, much as Pauling had.

“He knows the power that it has over people, and that he can use that for the greater good,” Moss says. “He refers to it as his ‘pixie dust.’ It’s like this little magical power that he has.”

Agre did not hesitate to use that power to advance the work of the JHMRI, where he was finally able to fulfill his goal of addressing diseases of the developing world.

“I had been waiting to get into malaria,” says Agre, who made frequent trips to Zambia, Zimbabwe, and the Democratic Republic of Congo to support the work that Institute scientists and their African partners were doing in the field to better understand and control the disease.

Science diplomacy may have presented the ideal venue to scatter his pixie dust, however. The North Koreans, for example, were reportedly hesitant to receive a Western scientific delegation until they learned that a Nobel laureate would be leading it. And Agre had other qualities that made him uniquely well-equipped to handle the hardest diplomatic cases.

“He’s a very unusual person,” says Linda Staheli, a veteran science diplomat who led the DPRK Science Engagement Consortium that organized Agre’s first trip to Pyongyang. (Staheli recently produced a documentary about U.S. scientific engagement with North Korea, A Peace of Science, in which Agre features prominently.) In her telling, Agre blends scientific credibility with a genuine interest in policy and impeccable soft skills—a rare and powerful combination that has made him a kingpin of U.S. science diplomacy. “He is so easy to engage with, so warm and funny, and gets the people-to-people stuff,” she says.

The “people-to-people stuff” turned out to be particularly important. The AAAS delegations that Agre led abroad between 2009 and 2012 set out to explore the possibility of cooperating in uncontroversial areas of mutual interest like agriculture, health, and environmental science. But given the lack of familiarity between the various parties, the primary goal was simply to build sufficient trust to continue the conversation.

“I was hoping to establish friendships,” Agre says.

The North Korea mission, for instance, represented the first time that a U.S. science delegation had visited the country; and while the North Koreans were hoping to gain access to American resources, most had never actually met an American before. One of the delegation’s official chaperones confided to Agre that when he told his grandson that he would be meeting a bunch of Americans in Pyongyang, the little boy responded, “Grandfather, bring the rifle.”

Yet Agre bridged the divide through charm, humor, and simple acts of humanity: Singing the periodic table during a formal toast to high-ranking officials; dancing to Madonna’s version of “American Pie” during a demonstration of audio equipment in the Grand People’s Hall of Study (the North Korean equivalent of the Library of Congress); presenting the tie he wore while delivering his Nobel lecture to the vice president of the State Academy of Science, so that he could someday give it to the first North Korean to win a Nobel.

By the end of that trip, the two sides were sharing stories of their families and their hopes for the future. “Our chaperones became our friends,” Agre says. According to Staheli, it was Agre’s involvement that led the North Koreans to sign a memorandum of understanding formalizing their willingness to pursue potential collaborations. That goodwill led to additional meetings in the U.S. and Italy, and ultimately to a program to teach English to North Korean scientists and the creation of a virtual science library to grant them access to Western science journals.

Yet Agre is realistic about the limits of science diplomacy, which is inevitably subject to the vicissitudes of global politics. Although he made several subsequent trips to North Korea to visit Pyongyang University of Science and Technology, worsening relations between the U.S. and the DPRK have prevented him from returning since 2015. And he has yet to revisit Iran, despite having been given an office at Sharif University of Technology in Tehran on the condition that he return for 10 days of lectures and scholarly activity every year. “I’ve been in touch with them,” Agre says. “But it’s just not safe.”

Even in Cuba, the country where the greatest inroads have been made, results have been mixed. Agre has visited the island nearly a dozen times, has met with President Miguel Díaz-Canel in both Havana and New York, and has arranged for Cuban researchers to attend the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings, an annual gathering in Germany of Nobel laureates and young scientists. Moreover, Cuban scientists, including members of the Castro family, have visited the School, taught classes at Hopkins, and spent time at the JHMRI; while the AAAS and the Cuban Academy of Sciences have convened symposia in Havana on neuroscience, cancer immunotherapy, and mosquito-borne illnesses. Yet prickly relations between successive U.S. and Cuban administrations still make sustained collaborations difficult.

Nonetheless, Agre remains committed to using science as a means of fostering international cooperation and understanding. "I would like to see more exchange; I’d like to see more partnerships," he says, adding that science diplomacy need not be limited to situations where diplomatic relations are poor, but can be practiced anywhere, from Libya to Finland.

Agre himself seems to prefer the toughest cases, however. “I’m a little bit of the opinion we should be looking for things that are hard to do,” he says. While he claims to have slowed down somewhat—he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease 12 years ago and tires more easily than he once did—his schedule suggests otherwise: He met with an Iranian contact while visiting the University of Arizona in February, zipped back down to Washington to attend another event organized by the Johns Hopkins Science Policy and Diplomacy Group a couple of weeks later, and returned to Cuba to speak at an AAAS event in March. Yet if his unflagging dedication to science diplomacy is idealistic in the best sense of the word—“there’s no reason not to try,” he says—it is also highly pragmatic.

For one thing, experience has taught Agre that even governments hostile to the U.S. tend to welcome American scientists. “I think they see us as maybe harmless, possibly even better,” he says. What’s more, even the most oppressive regimes harbor talented and well-meaning scientists; and when those regimes collapse, as Agre believes they eventually will, “there are competent people we should know.”

For another, there are under-resourced parts of the world where the close partnerships and scientist-to-scientist interactions that science diplomacy seeks to cultivate represent the best hope for making progress on pressing global health issues.

“I think it’s the best entry into Africa,” says Agre, who points to the JHMRI’s successful malaria research and control efforts undertaken with African scientists and physicians. Collaborations between the Institute and the Macha Research Trust in Zambia, for example, have contributed to the reduction of malaria cases in the area by more than 95%.

From that perspective, science diplomacy represents a unique tool for advancing public health. The obstacles may be significant and the rewards uncertain, but Agre has never been one to shy away from a challenge.

“If I’d wanted to play it safe,” he says, “I would have never left Minnesota.”

Connection Points

Over the years and across the globe, Peter Agre has been building bridges between cultures through his public health work.

-

2009

At Pyongyang University of Science and Technology

-

2010

With Deputy Health Minster of Burma (Myanmar) Mya Oo

-

2012

At Tehran University of Medical Sciences

-

2013

In Macha, Zambia

-

2015

At the Cuba Academy of Sciences, Havana

-

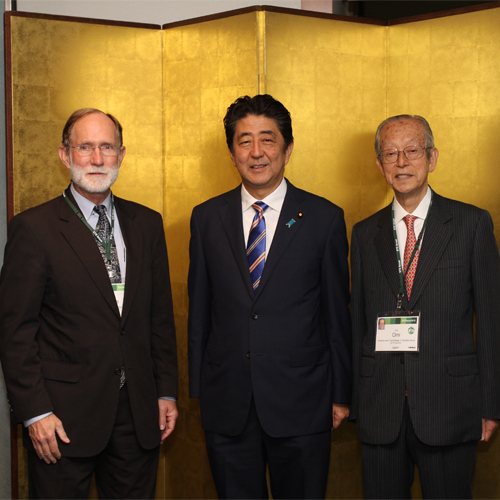

2016

With Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

-

2023

With Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi

-

2023

With Cuban President Miguel Diaz-Canel