The Blue Death

All things considered, that September found William Henry Welch in a satisfied state of mind. The Johns Hopkins physician-scientist was Lieutenant-Colonel Welch now, having responded to the call of a country gearing up for war.

The previous weeks had passed in an inspection tour of hastily assembled military camps around the country, where he had been treated with the deference due a man who was serving, simultaneously, as president of the National Academy of Sciences, the Rockefeller Institute and the Carnegie Institution.

Welch had done what he could. “The medical service of the army is now well organized,” he wrote, “and conditions are very much improved in our camps.”

Thinking his work largely done, Welch mused about resigning from the army. He wanted to devote all his energies to the opening of a new School of Hygiene and Public Health at Hopkins. At the end of his inspection tour, he indulged himself with a few days in the North Carolina hills.

“It is a delightful, restful, quiet place,” he wrote on September 19. Those days at the Mountain Meadows Inn would be the last bit of peace Welch would enjoy for some time. On September 22, he was ordered to Massachusetts, where a strange, virulent influenza had taken hold at Camp Devens. The year, of course, was 1918.

No matter how many times the numbers get trotted out, they seem beyond comprehension. The global death toll from the 1918 flu was long pegged at 20 million, but most experts now think that grossly low. They talk of 50 million, perhaps 100 million.

“If you’re in the business of infectious disease epidemics, you can’t ignore the 1918 flu—it’s the granddaddy of them all,” says the Bloomberg School’s Donald Burke, professor of International Health.

Yet much about the pandemic remains unsettled, particularly the mystery surrounding the shape of the flu’s devastation. In a normal flu epidemic, a graph of fatalities looks like the letter U, with the twin peaks representing a heavy toll among young children and the frail elderly. That graph of the 1918 flu looks more like a misshapen W, with an astonishing middle peak reflecting that it was most fatal to perfectly healthy adults in their 20s and 30s.

Burke and Derek Cummings, a PhD candidate in International Health, are looking at yet another murky area: How, precisely, did the disease travel through the population? Did it follow patterns that correspond with age or ethnic group or social class? Did it take a predictable path from inner city to outer, from urban center to rural outpost, from military camp to civilian population?

Such questions are not academic in a post–September 11 world. The National Institutes of Health is financing this research as one of its MIDAS (Models of Infectious Disease Agent Study) projects to help prepare for biological warfare. But the import of the work goes beyond national security.

“Of all the potential infectious disease threats, I worry about this one more than any other,” Burke says. “When it comes to the probability of a pandemic of flu, I think everyone would say, ‘It’s not if, it’s when.’

“Where is the next virus going to come from? The three possibilities are a natural emergence, bioterrorism and what I call biobungling—that’s when somebody in a lab messes up. There are flu viruses sitting around in who-knows-how-many freezers today. Some of those viruses are extinct—they should be high-containment agents. Yet they’re sitting around, unlocked. If I had to choose which of the possibilities was most likely, I’d go with biobungling.”

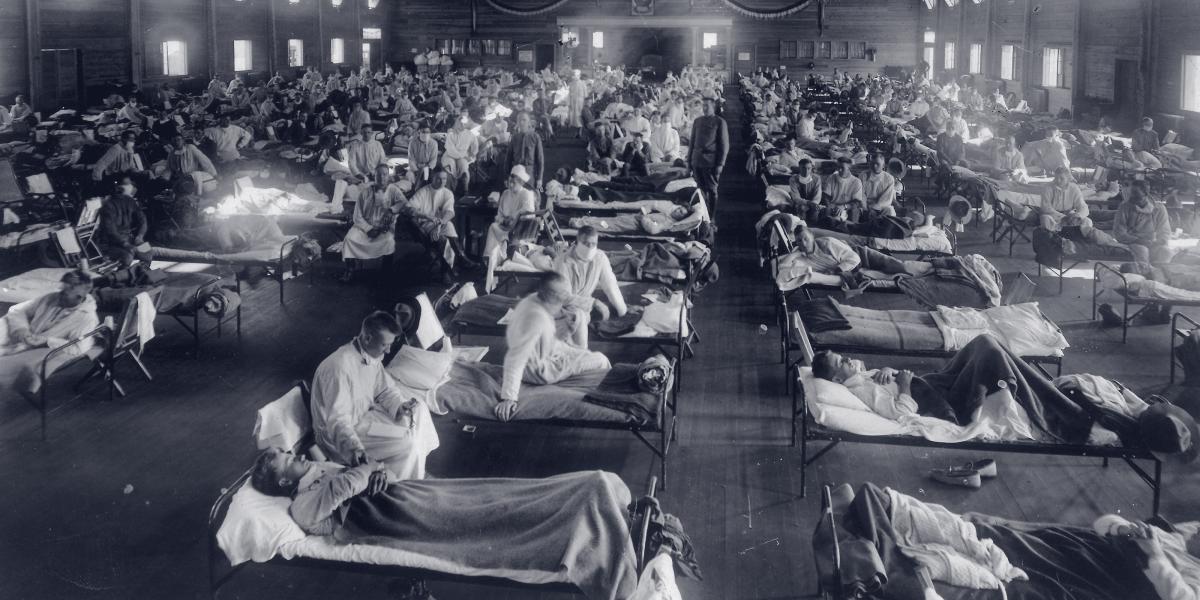

Camp Devens was a nightmare of rasping blue death. Lines of men clutching blankets stood outside the hospital in the rain. Inside, cots overflowed into hallways and onto porches. Many patients had the deadly hue of cyanosis, a blue so deep that many observers misjudged this for the return of “black death.” In the morgue, Welch and Cole had to step over and around piles of corpses to observe an autopsy.

Cole later recalled: “When the chest was opened and the blue swollen lungs were removed and opened, and Dr. Welch saw the wet, foamy surfaces with real consolidation, he turned and said, ‘This must be some new kind of infection or plague,’ and he was quite excited and obviously very nervous... It was not surprising that the rest of us were disturbed, but it shocked me to find that the situation, momentarily at least, was too much even for Dr. Welch.”

The physicians quickly recovered their equilibrium. Welch called in an expert from Harvard to perform autopsies. He ordered a Rockefeller lab scientist to drop everything and make a vaccine. He told the army to order camp hospitals expanded and to impose quarantine measures.

It was too little, too late. Flu victims were contagious for several days before showing symptoms, and soldiers had been flowing in and out of Devens daily, as had civilian staff and volunteers. The influenza virus soon appeared in Boston, in Philadelphia, in New York and in New Orleans.

Most victims recovered, and their experience generally was a more intense version of the expected weeklong course of fever, aches, chills and nausea. But a substantial minority endured much worse. They were utterly incapacitated by exhaustion, able to summon up the energy only to cry out constantly in the face of excruciating earaches and headaches.

As the disease progressed and pneumonia set in, they began to bleed profusely—from the nose, the ear and the mouth. Some still recovered. Hopkins physician Harvey Cushing was one such case. But if cyanosis appeared, physicians treated patients as terminal. Autopsies would show a disease that ravaged almost every internal organ.

Baltimore had scant warning that this flu was coming. On September 18 the Baltimore News reported the appearance of “Spanish flu” in New England.

In a flash, the flu was at Fort Meade and at Camp Holabird. A week later, it had hit the city. The News, in a Sept. 29 editorial: “While there is undoubtedly danger of its proving fatal in some cases, there is little likelihood of its being comparable with the plagues... in past centuries.”

With benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to see here the crux of a critical problem in the weeks ahead. There was a war on, and, right or wrong, the war would take priority. Shipyards had to keep working, troop ships had to keep moving, and homeland morale had to stay high. Politicians, the media and even public health officials either couldn’t or wouldn’t communicate frankly. (more)

On October 1, 119 new cases were reported; on October 4, 400. Asked about closing schools and banning public gatherings, the city’s health commissioner told the Baltimore Sun, “Drastic measures…only excite people, throw them into a nervous state and lower their resistance to disease.”

On October 10, the number of new cases peaked at 1,962. The rising death toll was proof, the News said, that the epidemic was reaching a “climax” and “may be expected to fall sharply soon.”

Everyone was out sick. There were too few milkmen, too few firefighters, too few telephone operators and too few gravediggers. The city didn’t have enough workers to process death certificates. As it was illegal to conduct burials without one, bodies and caskets stacked up inside—and outside—funeral homes.

Hospitals were overwhelmed. At Johns Hopkins Hospital, as the scope of the epidemic widened, flu patients occupied six full wards, and then the Hospital had to close its doors altogether. Three staff physicians, three medical students and six nurses died in the epidemic.

Scenes of heartbreaking loss were replayed in city after city around the country—and the world. Stell Altman was 9 years old at the time and living in Rochester, New York. She, her three younger siblings, and her mother were all stricken, but, miraculously, her father remained healthy and cared for his bedridden family.

“I don’t know what would have happened if my father had gotten sick,” says Altman, who is now 95 and whose nephew, Shale Stiller, is a Johns Hopkins University trustee. “There was no help to be found anywhere; everyone was too busy caring for their own families.” Altman’s mother, Sarah Salitan, died. Her father, Morris, laid his wife’s body on a bed of straw in the home, in accord with Jewish customs.

“We children didn’t go to the cemetery,” Altman says. “We were all still sick in bed.”

Like most other cities in the region, Baltimore slowly came around to sterner measures, closing schools and outlawing public gatherings. Whether such steps made a difference or the epidemic simply ran its course is difficult to say. The flu faded in November, then lingered into early 1919.

Reporting errors and recordkeeping lapses make reliable estimates of Baltimore’s flu cases and fatalities hard to come by. By the most conservative of counts, at least 75,000 of the city’s 600,000 residents caught the flu, and more than 2,000 of those died. In an ordinary October in the early 20th century, Baltimore would suffer fewer than five deaths caused by influenza. In October of 1918, it suffered 1,464.

The story of how Burke and Cummings came to mine the numbers of the 1918 flu epidemic begins in distant Thailand, where mosquito-borne dengue fever is endemic. Recently, Cummings and colleagues took data covering 850,000 cases over 15 years of dengue hemorrhagic fever, the most deadly form of the disease, and ran them through a mathematical technique originally developed by NASA to study physical waves, like in water and sound. The results were published earlier this year in Nature.

“What we found is this repeating, radial pattern,” Cummings says. “Every three years, this wave moves through the country, and it comes out of Bangkok, right in the middle.”

Cummings is pushing this work further, trying to identify the forces driving the spatial and temporal dynamics of the wave. But simply detecting it has important implications for public health.

“It tells you two things,” Burke says. “One is, if you’re in one of the outer zones, all you’ve got to do is monitor Bangkok to know you need to prepare for an epidemic. There could be a six- or eight-month lead time. The second thing is, if we do something that succeeds in Bangkok, we may accomplish something important for the whole country.”

No one has ever looked at pandemic flu data in this way before. It will be a challenge gathering reliable data in the requisite detail, but Cummings’ search is under way in Maryland—from there, he plans to fan out along the Eastern seaboard.

At a minimum, pinpointing predictable ways pandemic flu rolls through space and time could offer information that helps “downstream” communities prepare for its arrival, Burke says. But it could also prove vital on the front lines. The tools in place to fight a flu pandemic today aren’t that different from the ones Welch and his colleagues employed. Hospital and isolation facilities are improved, of course. Antiviral medicines would help, but stockpiles would disappear rapidly in an event approaching the scale of 1918. So, too, would the world’s 200 million or so doses of flu vaccine.

“We can use information like this in designing intervention strategies,” Burke says. “If we immunize young people, will that slow down the epidemic and give us time to make more vaccine? What if we vaccinated the more mobile sectors of society? Are there things we can learn here that would help us make the most rational use of our limited resources? My belief is yes, there are.”

On the way back to Baltimore from Camp Devens, William Henry Welch fell victim to the flu. Years later, Welch told colleagues at a conference, “I could not have dreamed of going to a hospital at that time.”

Instead, the 67-year-old returned to the rooms he rented in Mount Vernon, went to bed and stayed there.

“The condition of Lieutenant-Colonel William H. Welch, of the Johns Hopkins University,…who for some days has been confined to his rooms, suffering from an attack of influenza, was said to be greatly improved yesterday,” the Baltimore Suninformed readers on October 14. “…It was stated last evening that he expected to sit up today and to resume his duties in Washington in the near future.”

When he finally felt well enough to travel, Welch journeyed instead to his favorite vacation spot, the Hotel Dennis in Atlantic City.

At least six weeks passed before he finally felt well enough to get back to his military duties and to that business of opening a new School of Hygiene and Public Health.